This annotated version by Adrian Freed borrows some ideas from medieval glosses. It is intented to provide context and readability unavailable in the original pdf.

programming

Managing Complexity with Explicit Mapping of Gestures to Sound Control with OSC

Fri, 03/12/2021 - 13:32 — AdrianFreedManaging Complexity

with Explicit Mapping of Gestures to Sound Control

with OSC

Matthew Wright

Adrian Freed

Ahm Lee

Tim Madden

Ali Momeni

email: {matt,adrian,ahm,tjmadden,ali}@cnmat.berkeley.edu

Open Sound Control (OSC) offers much to the

creators of these gesture-to-sound-control mappings: It is general enough to

represent both the sensed gestures from physical controllers and the parameter

settings needed to control sound synthesis. It provides a uniform syntax

and conceptual framework for this mapping. The symbolic names for all OSC

parameters make explicit what is being controlled and can make programs easier

to read and understand. An OSC interface to a gestural-sensing or

signal-processing subprogram is an effective form of abstraction that exposes

pertinent features while hiding the complexities of implementation.

We present a paradigm for using OSC for mapping tasks and describe a

series of examples culled from several years of live performance with a

variety of gestural controllers and performance paradigms.

Open Sound Control (OSC) was originally developed to facilitate the

distribution of control-structure computations to small arrays of loosely-coupled heterogeneous computer systems.

A common application of OSC is to

communicate control-structure computations from one client machine to an array

of synthesis servers. The abstraction mechanisms built into OSC, a

hierarchical name space and regular-expression message dispatch, are also useful

in implementations running entirely on a single

machine. In this situation we have adapted the OSC client/server model to the organization of the gestural

component of control-structure computations.

The basic strategy is to:

Now the gestural performance mapping is simply a translation of one set of

OSC messages to another. This gives performers greater scope and facility in

choosing how best to effect the required parameter changes.

Wacom digitizing graphic tablets are attractive gestural interfaces for

real-time computer music. They provide extremely accurate two-dimensional

absolute position sensing of a stylus, along with measurements of pressure,

two-dimensional tilt, and the state of the switches on the side of the stylus,

with reasonably low latency. The styli (pens) are two-sided, with a

tip and an eraser.;

The tablets also support other

devices, including a mouse-like puck, and can be used with two

devices simultaneously.

Unfortunately, this measurement data comes from the Wacom drivers in an inconvenient form. Each

of the five continuous parameters is available independently, but another parameter,

the device type, indicates what kind of device is being used and,

for the case of pens, whether the tip or eraser is being used. For a program to

have different behavior based on which end of the pen is used, there must be a

switching and gating mechanism to route the continuous parameters to the correct

processing based on the device type. Similarly, the tablet senses

position and tilt even when the pen is not touching the tablet, so a program that

behaves differently based on whether or not the pen is touching the tablet must

examine another variable to properly dispatch the continuous parameters. Instead of simply providing the raw data from the Wacom drivers, our

At the moment the eraser end of the pen is released from the tablet,

With this scheme, all of the dispatching on the device type

variables is done once and for all inside We use another level of OSC addressing to define

distinct behaviors for different regions of the tablet. The interface designer

creates a data structure giving the names and locations of any number of regions

on the tablet surface. An object called For example, suppose the pen is drawing within a region named

foo. Once again tedious programming work is hidden from the interface designer,

whose job is simply to take OSC messages describing tablet gestures and map

them to musical control. Tactex's MTC Express controller senses pressure at multiple points on

a surface. The primary challenge using the device is to reduce the high

dimensionality of the raw sensor output (over a hundred pressure values) to a

small number of parameters that can be reliably controlled. One approach is to install physical

tactile guides over the surface and interpret the result as a set of sliders controlled

by a performer's fingers. Apart from not fully exploiting the potential of

the controller this approach has the disadvantage of introducing delays as the

performer finds the slider positions. An alternative approach

is to interpret the output of the tactile array as an image and use

computer vision techniques to estimate pressure for each finger of the hand. Software

provided by Tactex outputs four parameters for each of up to five sensed fingers,

which we represent with the following OSC addresses:

The anatomy of the human hand makes it impossible to control these four

variables independently for each of five fingers. We have developed another

level of analysis, based on interpreting the parameters of three fingers as a

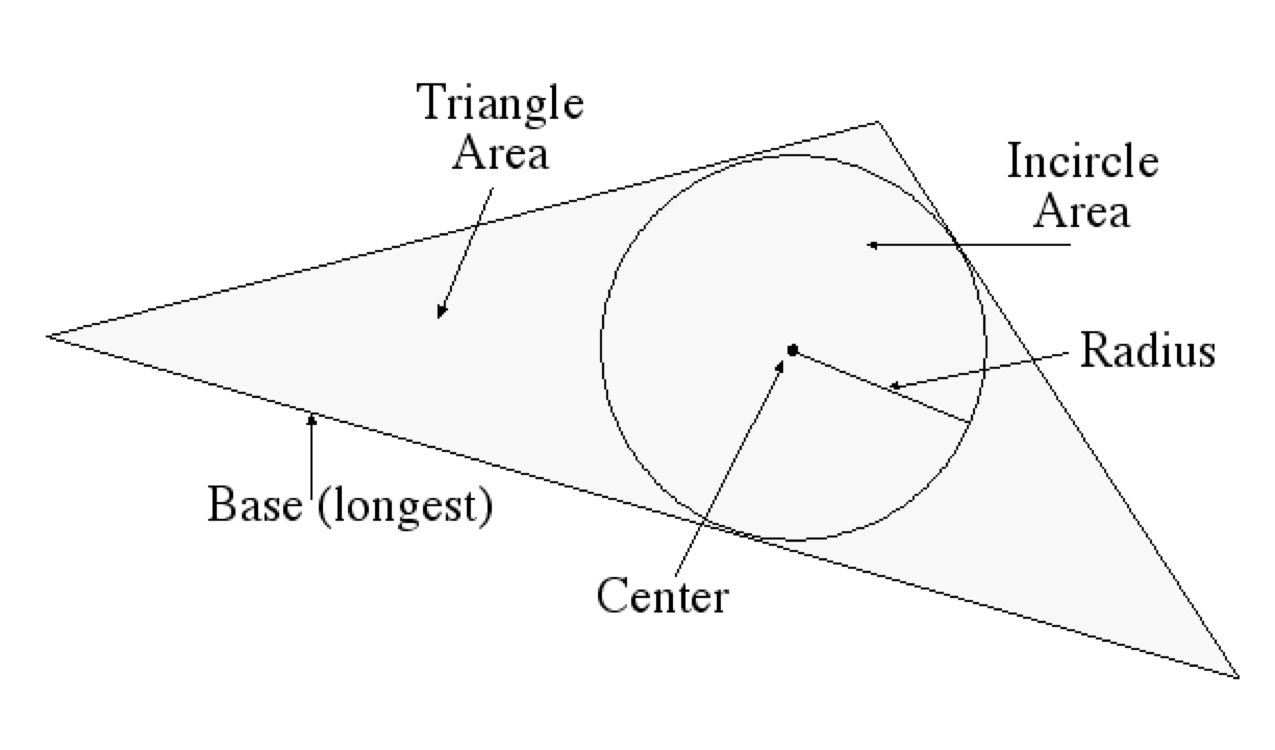

triangle, as shown below. This results in the parameters listed below.

These parameters are particularly easy to control and were chosen because they work

with any orientation of the hand. USB joysticks used for computer games also have good properties as musical

controllers. One model senses two dimensions of tilt, rotation of the

joystick, and a large array of buttons and switches. The buttons support

chording, meaning that multiple buttons can be pressed at once and

detected individually. We developed a modal interface in which each button corresponds to a particular musical

behavior. With no buttons pressed, no sound results. When one or more buttons

are pressed, the joystick's tilt and rotation continuously affect the behaviors

associated with those buttons. The raw joystick data is converted into OSC messages whose address

indicates which button is pressed and whose arguments give the current

continuous measurements of the joystick’s state. When two or more buttons

are depressed, the mapper outputs one OSC message per depressed button, each

having identical arguments. For example, while buttons B and

D are pressed, our software continuously outputs these two

messages: Messages with the address Suppose a computer-music instrument is to be controlled by two keyboards,

two continuous foot-pedals, and a foot- switch. There is no reason for the

designer of this instrument to think about which MIDI channels will be used,

which MIDI controller numbers the foot-pedals output, whether the input comes

to the computer on one or more MIDI ports, etc. We map MIDI message to OSC messages as soon as possible. Only the part of

the program which does this translation needs to embody any of the MIDI

addressing details listed above. The rest of the program sees messages with

symbolic names like The use of an explicit mapping from gestural input to sound control, both

represented as OSC messages, makes it easy to change this mapping in real-time

to create different modes of behavior for an instrument. Simply route incoming

OSC messages to the mapping software corresponding to the current mode. For example, we have developed Wacom tablet interfaces where the region in

which the pen touches the tablet surface defines a musical behavior to be

controlled by the continuous pen parameters even as the pen moves outside the

original region. Selection of a region when the pen touches the tablet

determines which mapper(s) will interpret the continuous pen parameters until

the pen is released from the tablet. We have created a large body of signal processing instruments that

transform the hexaphonic output of an electric guitar. Many of these effects

are structured as groups of 6 signal-processing modules, one for each string,

with individual control of all parameters on a per-string basis. For example,

a hexaphonic 4-tap delay has 6 signal inputs, 6 signal outputs, and six groups

of nine parameters: the gain of the undelayed signal, four tap times, and

four tap gains. OSC gives us a clean way to organize these 54 parameters. We make an

address space whose top level chooses one of the six delay lines with the

numerals 1-6, and whose bottom level names the parameters. For example, the

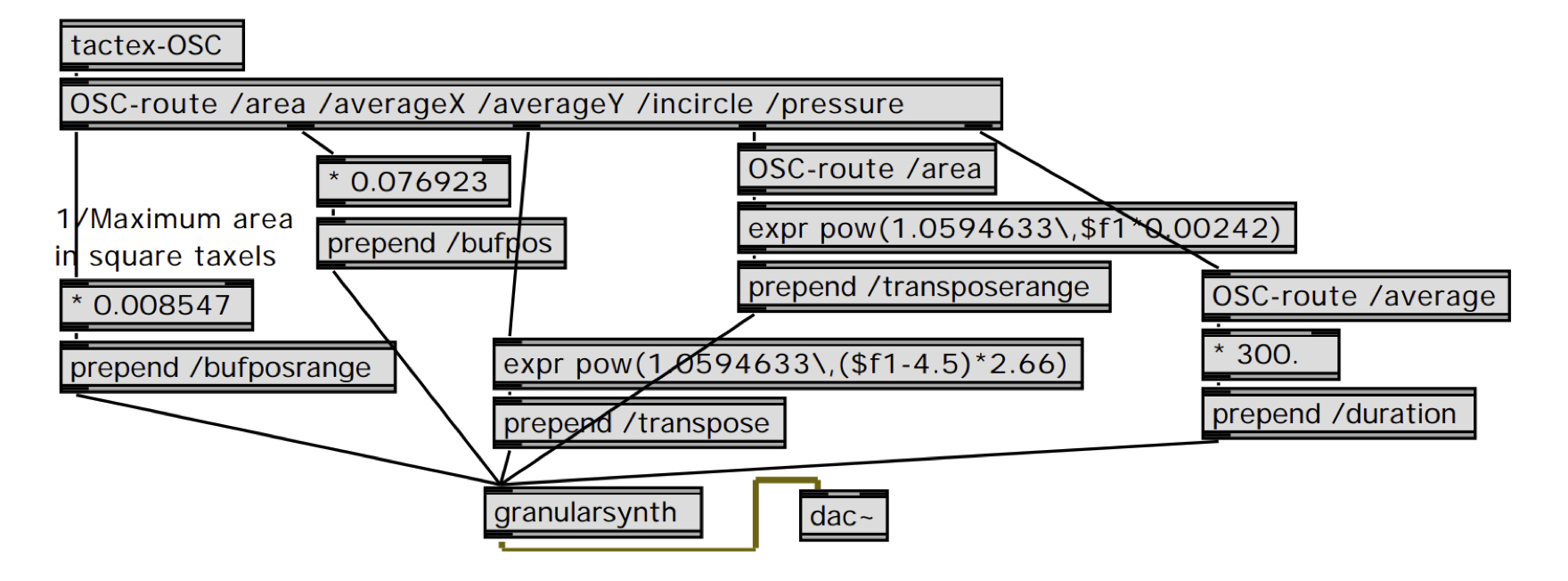

address We have developed an interface that controls granular synthesis from the

triangle-detection software for the Tactex MTC described above. Our granular

synthesis instrument continuously synthesizes grains each with a location in

the original sound and frequency transposition value that are chosen randomly

from within a range of possible values. The real-time-controllable parameters

of this instrument are arranged in a straightforward OSC address

space: The Max/MSP patch shown below maps incoming Tactex

triangle-detection OSC messages to OSC messages to control this granular

synthesizer.

This mapping was codeveloped with Guitarist/Composer John Schott and used

for his composition The Fly.

We have described the benefits in diverse contexts of explicit mapping of

gestures to sound control parameters with OSC.

UC Berkeley

1750 Arch St.

Berkeley, CA 94709, USA

Abstract

We present a novel use of the OSC protocol to represent the output

of gestural controllers as well as the input to sound synthesis processes. With

this scheme, the problem of mapping gestural input into sound synthesis control

becomes a simple translation from OSC messages into other OSC messages. We provide

examples of this strategy and show benefits including increased encapsulation

and program clarity.

Introduction

Shafqat Ali Kahn

Matt Wright (R)

Open Sound Control

An OSC Address Subspace for Wacom Tablet Data

/{tip, eraser}/{hovering, drawing} x y xtilt ytilt pressure

/{tip, eraser}/{touch, release} x y xtilt ytilt

/{airbrush, puckWheel, puckRotation} value

/buttons/[1-2] booleanValue

Wacom-OSC object outputs OSC messages with different addresses for the

different states. For example, if the eraser end of the pen is currently

touching the tablet, Wacom-OSC continuously outputs messages whose

address is /eraser/drawing and whose arguments are the current values of position, tilt, and pressure.

Wacom-OSC outputs the message /eraser/release. As long as the

eraser is within range of the tablet surface, Wacom-OSC continuously

outputs messages with the address /eraser/hovering and the same

position, tilt, and pressure arguments.Wacom-OSC, and hidden from

the interface designer. The interface designer simply uses the existing

mechanisms for routing OSC messages to map the different pen states to

different musical behaviors.Wacom-Regions takes the OSC messages

from Wacom-OSC and prepends the appropriate region name for events that

occur in the region. Wacom-OSC outputs the message /tip/drawing with

arguments giving the current pen position, tilt, and pressure.

Wacom-Regions looks up this current pen position in the data structure

of all the regions and sees that the pen is currently in region

foo so it outputs the message /foo/tip/drawing

with the same arguments. Now the standard OSC message routing mechanisms can

dispatch these messages to the part of the program that implements the

behavior of the region foo.

4. Dimensionality Reduction for the Tactex Control Surface

/area <area_of_inscribed_triangle>

/averageX <avg_X_value>

/averageY <avg_Y_value>

/incircle/radius <Incircle radius>

/incircle/area <Incircle area>

/sideLengths <side1> <side2> <side3>

/baseLength <length_of_longest_side>

/orientation <slope_of_longest_side>

/pressure/average <avg_pressure_value>

/pressure/max <maximum_pressure_value>

/pressure/min <minimum_pressure_value>

/pressure/tilt <leftmost_Z-rightmost_Z>

An OSC Address Space for Joysticks

/joystick/b xtilt

ytilt rotation/joystick/d xtilt

ytilt rotation/joystick/b

are then routed to the software implementing the behavior associated with

button B with the normal OSC message routing

mechanisms.Mapping Incoming MIDI to OSC

/footpedal1, so the

mapping of MIDI to synthesis control is clear and

self-documenting.Controller Remapping

OSC to Control Hexaphonic Guitar Processing

/3/tap2time sets the time of the

second delay tap for the third string. We can then leverage OSC’s

pattern-matching capabilities, for example,

by sending the message /[4-6]/tap[3-4]gain to set the gain of taps three

and four of strings four, five, and six all at once.Example: A Tactex-Controlled Granular Synthesis Instrument

Conclusion

References

Boie, B., M. Mathews, and A. Schloss 1989. The Radio Drum as a Synthesizer Controller. Proceedings of the International Computer Music Conference, Columbus, OH, pp. 42-45.

Buchla, D. 2001. Buchla Thunder. http://www.buchla.com/historical/thunder/index.html

Tactex. 2001. Tactex Controls Home Page. http://www.tactex.com

Wright, M. 1998. Implementation and Performance Issues with Open Sound Control. Proceedings of the International Computer Music Conference, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Wright, M. and A. Freed 1997. Open Sound Control: A New Protocol for Communicating with Sound Synthesizers. Proceedings of the International Computer Music Conference, Thessaloniki, Hellas, pp. 101-104.

Wright, M., D. Wessel, and A. Freed 1997. New Musical Control Structures from Standard Gestural Controllers. Proceedings of the International Computer Music Conference, Thessaloniki, Hellas.

C++ container output stream header file

Thu, 09/24/2020 - 16:30 — AdrianFreedAnalog and Digital Sound Synthesis as Relaxation Oscillators

Thu, 04/11/2019 - 16:40 — AdrianFreedThe following pages provide context for the workshop and include links to contributions from my co-teacher, Martin De Bie. This includes pointers to various iterations of his 555 timer-based Textilo project.

This project will be expanded ongoingly with further relaxation oscillator schemes.

Sound Making Technologies Ordered by Increasing Complexity/Cost/Size

Sun, 04/22/2018 - 14:36 — AdrianFreed| Approach | Example | Link |

|---|---|---|

| non-electronic | Lamello | http://bid.berkeley.edu/papers/chi/lamello_passive_acoustic_sensi/ |

| *Analog relaxation oscillator | Textilo | http://www.martindebie.com/research_project/textilo/ |

| Analog harmonic oscillator | self-resonating VCF | http://electronotes.netfirms.com/EN215.pdf |

| *Digital relaxation oscillator | Arduino Tone | https://github.com/adrianfreed/FastTouch |

| *Digital relaxation oscillator | Mozzi (LUT) | https://github.com/sensorium/Mozzi/blob/master/examples/01.Basics/Sinewa... |

| *Digital Modulation Synthesis | Mozzi (FM) | https://github.com/sensorium/Mozzi/tree/master/examples/06.Synthesis/FMs... |

| *Digital Subtractive Synthesis | Talkie (LPC Speech and singing) |

https://github.com/adrianfreed/Talkie |

| Unit Generator Library | Teensy Audio Library | https://www.pjrc.com/teensy/td_libs_Audio.html |

| Sampling "Synthesis" | Tone.js (Tone.Player) | https://tonejs.github.io |

| Dynamically Patched Unit Generators | Bela (libpd) | https://bela.io |

| Dynamically Patched Unit Generators with Image Synthesis |

Max/MSP/Jitter | https://cycling74.com/products/max |

| Analog Patched Modular | Modular | https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Modular_synthesizer |

FastTouch Open Source Arduino Library for Fast, Portable, Low Fidelity Capacitive Sensing

Sun, 04/22/2018 - 12:40 — AdrianFreedThe example code provided with the library uses the Arduino Tone library to sound pitches according to which pins are touched.

Notice that each call to the fast touch library implements a cycle of a relaxation oscillator.

I am indebted to Alice Giordani for exemplifying use of the library so well in this dreamcatcher:

Introduction to Relaxation Oscillators

Wed, 04/11/2018 - 16:20 — AdrianFreedPervasive Cameras: Making Sense of Many Angles using Radial Basis Function Interpolation and Salience Analysis

Mon, 01/15/2018 - 14:38 — AdrianFreedPervasive Cameras: Making Sense of Many Angles using Radial Basis Function Interpolation and Salients Analysis

Abstract. This paper describes situations which lend themselves to the use of numerous cameras and techniques for displaying many camera streams simultaneously. The focus here is on the role of the “director” in sorting out the onscreen content in an artistic and understandable manner. We describe techniques which we have employed in a system designed for capturing and displaying many video feeds incorporating automated and high level control of the composition on the screen.

1 A Hypothetical Cooking Show

A typical television cooking show might include a number of cameras capturing the action and techniques on stage from a variety of angles. If the TV chef were making salsa for example, cameras and crew might be setup by the sink to get a vegetable washing scene, over the cutting board to capture the cutting technique, next to a mixing bowl to show the finished salsa, and a few varying wider angle shots which can focus on the chef's face while he or she explains the process or on the kitchen scene as a whole. The director of such a show would then choose the series of angles that best visually describe the process and technique of making salsa. Now imagine trying to make a live cooking show presentation of the same recipe by oneself. Instead of a team of camera people, the prospective chef could simply setup a bunch of high quality and inexpensive webcams in these key positions in one's own kitchen to capture your process and banter from many angles. Along with the role of star, one must also act as director and compose these many angles into a cohesive and understandable narrative for the live audience.

Here we describe techniques for displaying many simultaneous video streams using automated and high level control of the cameras' positions and frame sizes on the screen allowing a solo director to compose many angles quickly, easily, and artistically.

2 Collage of Viewpoints

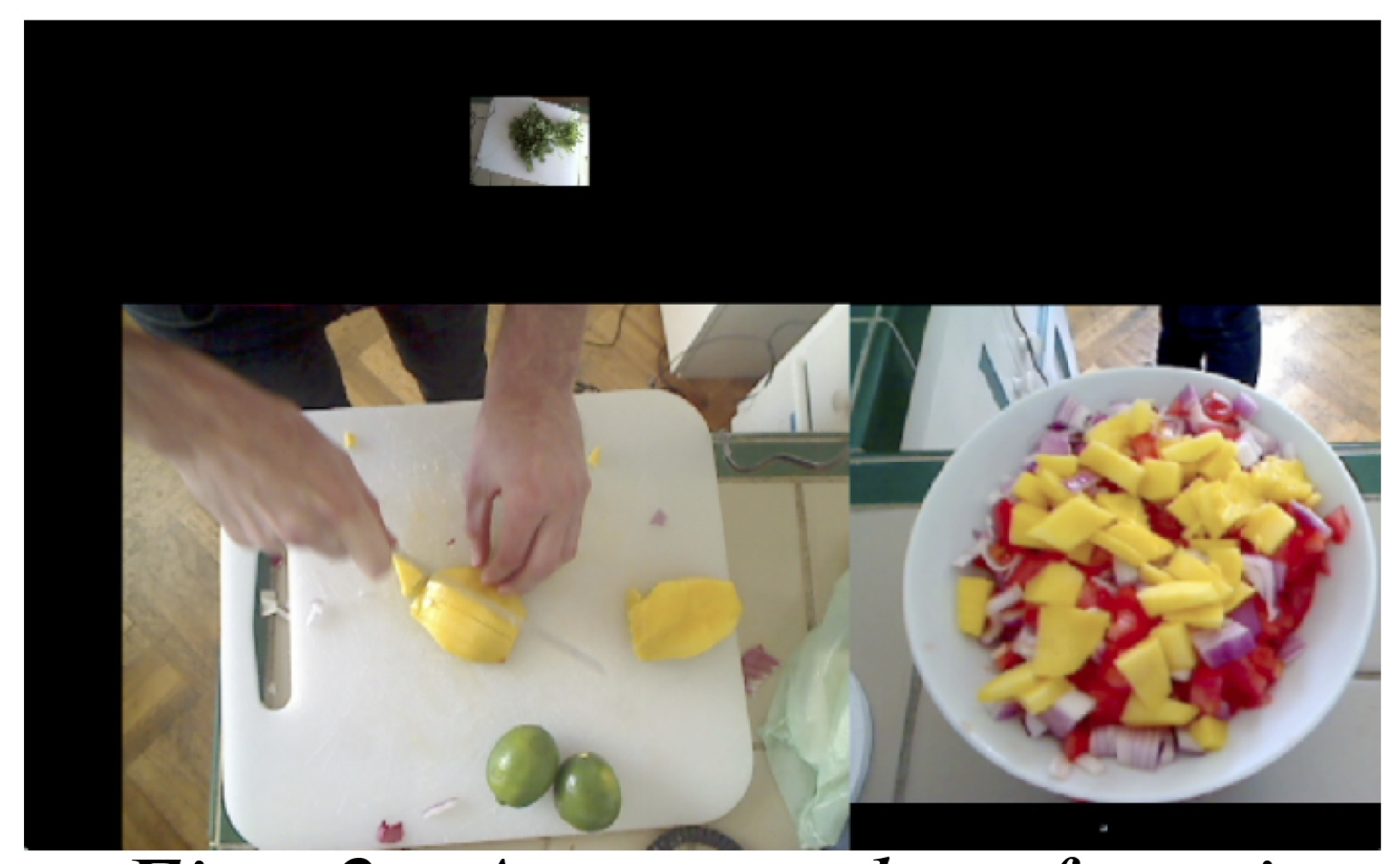

Cutting between multiple view points would possibly obscure one important aspect in favor of another. In the cooking show example, a picture in picture approach would allow the display of both a closeup of a tomato being chopped and the face of the chef describing his or her cutting technique. The multi angle approach is a powerful technique for understanding all of the action being captured in a scene as well as artistically compelling and greatly simplifies the work of the director of such a scene. The multi-camera setup lends itself to a collage of framed video streams on a single screen (fig. 1 shows an example of this multi-angle approach). We would like to avoid a security camera style display that would leave much of the screen filled with unimportant content, like a view of a sink not being used by anyone.

Figure 1: A shot focusing on the cilantro being washed

We focus attention on a single frame by making it larger than the surrounding frames or moving it closer to the center. The system is designed to take in a number of scaling factors (user-defined and automated) which multiply together to determine the final frame size and position. The user-defined scaling factor is set with a fader on each of the video channels. This is useful for setting initial level and biasing one frame over another in the overall mix. Setting and adjusting separate channels can be time consuming for the user, so we give a higher level of control to the user that facilitates scaling many video streams at once smoothly and quickly. CNMAT's (Center for New Music and Audio Technologies) rbfi (radial basis function interpolation) object for Max/MSP/Jitter allows the user to easily switch between preset arrangements, and also explore the infinite gradients in between these defined presets using interpolation[1]. rbfi lets the user place data points (presets in this case) anywhere in a 2 dimensional space and explore that space with a cursor. The weight of each preset is a power function of the distance from the cursor. For example, one preset point might enlarge all of the video frames on particular positions in the rooms, say by the kitchen island, so as the chef walks over the kitchen island, all of the cameras near the island enlarge and all of the other cameras shrink. Another preset might bias cameras focused on fruits. With rbfi, the user can slider the cursor to whichever preset best fits the current situation. With this simple, yet powerful high level of control, a user is able to compose the scene quickly and artistically, even while chopping onions.

Figure 2: A screenshot focusing

on the mango being chopped and

the mixing bowl

3 Automating Control

Another technique we employ is to automate the direction of the scene by analyzing the content of the individual frame and then resizing to maximize the area of the frame containing the most salient features. This approach makes for fluid and dynamic screen content which focuses on the action in the scene without any person needing to operate the controls. One such analysis measures the amount of motion which is quantified by taking a running average of the number of changed pixels between successive frames in one video stream. The most dynamic video stream would have the largest motion scaling factor while the others shrink from their relative lack of motion. Another analysis is detecting faces using the openCV library and then promoting video streams with faces in them. The multiplied combination of user-defined and automated weight adjustment determines each frames final size on the screen. Using these two automations with the cooking show example, if the chef looks up at the camera and starts chopping a tomato, the video streams that contain the chef's face and the tomato being chopped would be promoted to the largest frames in the scene while the other less important frames shrink to accommodate the two.

Figure 3: A screenshot of the

finished product and some

cleanup

Figure 3: A screenshot of the

finished product and some

cleanup

Positioning on the screen is also automated in this system. The frames are able to float anywhere on and off the screen while edge detection ensures that no frames overlap. The user sets the amount of a few different forces that are applied to the positions of the frames on the screen. One force propels all of the frame towards the center of the screen. Another force pushes the frames to rearrang their relative positions on the screen. No single influence dictates the exact positioning or size of any video frame; this is only determined by the complex interaction of all of these scaling factors and forces.

4 Telematic Example

Aside from a hypothetical self-made cooking show, a tested application of these techniques is in a telematic concert situation. The extensive use of webcams on the stage works well in a colocation concert where the audience might be in a remote location from the performers. Many angles on one scene gives the audience more of a tele-immersive experience. Audiences can also experience fine details like a performer's playing subtly inside the piano or a bassist's intricate fretboard work without having to be at the location or seated far from the stage. The potential issue is sorting out all of these video streams without overwhelming the viewer with content. This can be achieved without a large crew of videographers at each site, but with a single director dynamically resizing and rearranging the frames based on feel or cues as well as analysis of the video stream's content.

Figure 4: This is a view of a pianist from many angles which

would giving an audience a good understanding of the room

and all of the player's techniques inside the piano and on the

keyboard.

References

1. Freed, A., MacCallum, J., Schmeder, A., Wessel, D.: Visualizations and Interaction Strategies for Hybridization Interfaces. New Instruments for Musical Expression (2010)

Pervasive Cameras: Making Sense of Many Angles using Radial Basis Function Interpolation and Salience Analysis, , Pervasive 2011, 12/06/2011, San Francisco, CA, (2011)