This annotated version by Adrian Freed borrows some ideas from medieval glosses. It is intented to provide context and readability unavailable in the original pdf.

Gesture Signal Processing

Semblance Typology of Entrainments

Sat, 11/08/2014 - 21:36 — AdrianFreedsynonym - together in meaning

synorogeny - form boundaries

conclude- close together

symptosis - fall together

symptomatic - happening together

symphesis - growing together

sympatria - in the same region

symmetrophilic - lover of collecting in pairs

synaleiphein - melt together

For an evaluation of various mathematical formalizations inspired by this entrainment work, check out this paper: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Rushil_Anirudh/publication/29991298... The ASU team successfully quantify the advantages of metrics such as the one I suggested (HyperComplex Signal Correlation) for dancing bodies where correlated rotations and displacement are in play.

Thanks to:

Managing Complexity with Explicit Mapping of Gestures to Sound Control with OSC

Fri, 03/12/2021 - 14:32 — AdrianFreedManaging Complexity

with Explicit Mapping of Gestures to Sound Control

with OSC

Matthew Wright

Adrian Freed

Ahm Lee

Tim Madden

Ali Momeni

email: {matt,adrian,ahm,tjmadden,ali}@cnmat.berkeley.edu

Open Sound Control (OSC) offers much to the

creators of these gesture-to-sound-control mappings: It is general enough to

represent both the sensed gestures from physical controllers and the parameter

settings needed to control sound synthesis. It provides a uniform syntax

and conceptual framework for this mapping. The symbolic names for all OSC

parameters make explicit what is being controlled and can make programs easier

to read and understand. An OSC interface to a gestural-sensing or

signal-processing subprogram is an effective form of abstraction that exposes

pertinent features while hiding the complexities of implementation.

We present a paradigm for using OSC for mapping tasks and describe a

series of examples culled from several years of live performance with a

variety of gestural controllers and performance paradigms.

Open Sound Control (OSC) was originally developed to facilitate the

distribution of control-structure computations to small arrays of loosely-coupled heterogeneous computer systems.

A common application of OSC is to

communicate control-structure computations from one client machine to an array

of synthesis servers. The abstraction mechanisms built into OSC, a

hierarchical name space and regular-expression message dispatch, are also useful

in implementations running entirely on a single

machine. In this situation we have adapted the OSC client/server model to the organization of the gestural

component of control-structure computations.

The basic strategy is to:

Now the gestural performance mapping is simply a translation of one set of

OSC messages to another. This gives performers greater scope and facility in

choosing how best to effect the required parameter changes.

Wacom digitizing graphic tablets are attractive gestural interfaces for

real-time computer music. They provide extremely accurate two-dimensional

absolute position sensing of a stylus, along with measurements of pressure,

two-dimensional tilt, and the state of the switches on the side of the stylus,

with reasonably low latency. The styli (pens) are two-sided, with a

tip and an eraser.;

The tablets also support other

devices, including a mouse-like puck, and can be used with two

devices simultaneously.

Unfortunately, this measurement data comes from the Wacom drivers in an inconvenient form. Each

of the five continuous parameters is available independently, but another parameter,

the device type, indicates what kind of device is being used and,

for the case of pens, whether the tip or eraser is being used. For a program to

have different behavior based on which end of the pen is used, there must be a

switching and gating mechanism to route the continuous parameters to the correct

processing based on the device type. Similarly, the tablet senses

position and tilt even when the pen is not touching the tablet, so a program that

behaves differently based on whether or not the pen is touching the tablet must

examine another variable to properly dispatch the continuous parameters. Instead of simply providing the raw data from the Wacom drivers, our

At the moment the eraser end of the pen is released from the tablet,

With this scheme, all of the dispatching on the device type

variables is done once and for all inside We use another level of OSC addressing to define

distinct behaviors for different regions of the tablet. The interface designer

creates a data structure giving the names and locations of any number of regions

on the tablet surface. An object called For example, suppose the pen is drawing within a region named

foo. Once again tedious programming work is hidden from the interface designer,

whose job is simply to take OSC messages describing tablet gestures and map

them to musical control. Tactex's MTC Express controller senses pressure at multiple points on

a surface. The primary challenge using the device is to reduce the high

dimensionality of the raw sensor output (over a hundred pressure values) to a

small number of parameters that can be reliably controlled. One approach is to install physical

tactile guides over the surface and interpret the result as a set of sliders controlled

by a performer's fingers. Apart from not fully exploiting the potential of

the controller this approach has the disadvantage of introducing delays as the

performer finds the slider positions. An alternative approach

is to interpret the output of the tactile array as an image and use

computer vision techniques to estimate pressure for each finger of the hand. Software

provided by Tactex outputs four parameters for each of up to five sensed fingers,

which we represent with the following OSC addresses:

The anatomy of the human hand makes it impossible to control these four

variables independently for each of five fingers. We have developed another

level of analysis, based on interpreting the parameters of three fingers as a

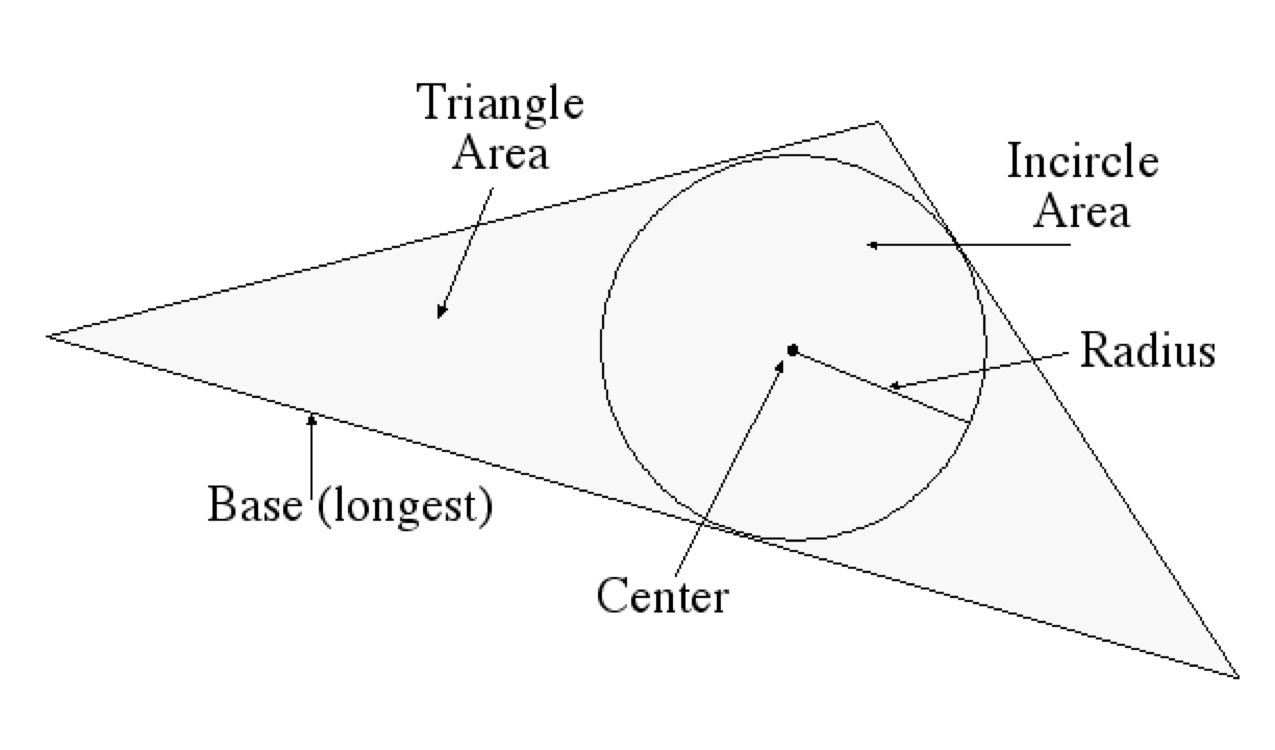

triangle, as shown below. This results in the parameters listed below.

These parameters are particularly easy to control and were chosen because they work

with any orientation of the hand. USB joysticks used for computer games also have good properties as musical

controllers. One model senses two dimensions of tilt, rotation of the

joystick, and a large array of buttons and switches. The buttons support

chording, meaning that multiple buttons can be pressed at once and

detected individually. We developed a modal interface in which each button corresponds to a particular musical

behavior. With no buttons pressed, no sound results. When one or more buttons

are pressed, the joystick's tilt and rotation continuously affect the behaviors

associated with those buttons. The raw joystick data is converted into OSC messages whose address

indicates which button is pressed and whose arguments give the current

continuous measurements of the joystick’s state. When two or more buttons

are depressed, the mapper outputs one OSC message per depressed button, each

having identical arguments. For example, while buttons B and

D are pressed, our software continuously outputs these two

messages: Messages with the address Suppose a computer-music instrument is to be controlled by two keyboards,

two continuous foot-pedals, and a foot- switch. There is no reason for the

designer of this instrument to think about which MIDI channels will be used,

which MIDI controller numbers the foot-pedals output, whether the input comes

to the computer on one or more MIDI ports, etc. We map MIDI message to OSC messages as soon as possible. Only the part of

the program which does this translation needs to embody any of the MIDI

addressing details listed above. The rest of the program sees messages with

symbolic names like The use of an explicit mapping from gestural input to sound control, both

represented as OSC messages, makes it easy to change this mapping in real-time

to create different modes of behavior for an instrument. Simply route incoming

OSC messages to the mapping software corresponding to the current mode. For example, we have developed Wacom tablet interfaces where the region in

which the pen touches the tablet surface defines a musical behavior to be

controlled by the continuous pen parameters even as the pen moves outside the

original region. Selection of a region when the pen touches the tablet

determines which mapper(s) will interpret the continuous pen parameters until

the pen is released from the tablet. We have created a large body of signal processing instruments that

transform the hexaphonic output of an electric guitar. Many of these effects

are structured as groups of 6 signal-processing modules, one for each string,

with individual control of all parameters on a per-string basis. For example,

a hexaphonic 4-tap delay has 6 signal inputs, 6 signal outputs, and six groups

of nine parameters: the gain of the undelayed signal, four tap times, and

four tap gains. OSC gives us a clean way to organize these 54 parameters. We make an

address space whose top level chooses one of the six delay lines with the

numerals 1-6, and whose bottom level names the parameters. For example, the

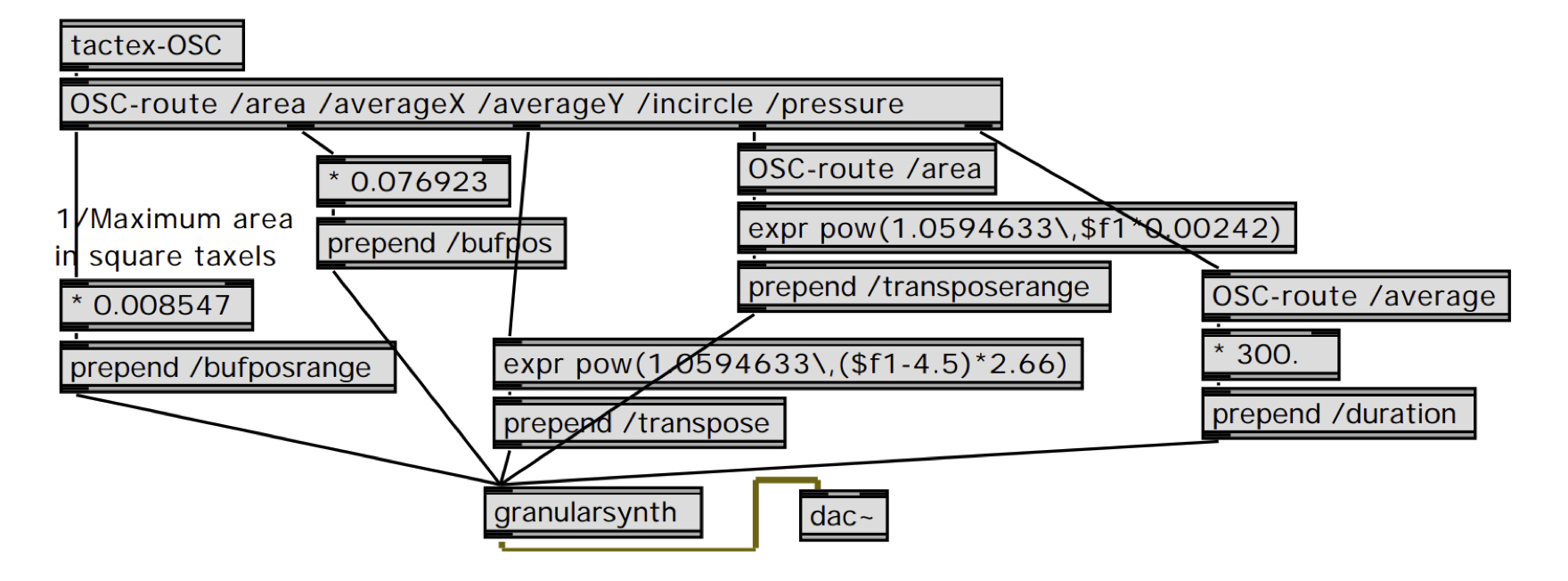

address We have developed an interface that controls granular synthesis from the

triangle-detection software for the Tactex MTC described above. Our granular

synthesis instrument continuously synthesizes grains each with a location in

the original sound and frequency transposition value that are chosen randomly

from within a range of possible values. The real-time-controllable parameters

of this instrument are arranged in a straightforward OSC address

space: The Max/MSP patch shown below maps incoming Tactex

triangle-detection OSC messages to OSC messages to control this granular

synthesizer.

This mapping was codeveloped with Guitarist/Composer John Schott and used

for his composition The Fly.

We have described the benefits in diverse contexts of explicit mapping of

gestures to sound control parameters with OSC.

UC Berkeley

1750 Arch St.

Berkeley, CA 94709, USA

Abstract

We present a novel use of the OSC protocol to represent the output

of gestural controllers as well as the input to sound synthesis processes. With

this scheme, the problem of mapping gestural input into sound synthesis control

becomes a simple translation from OSC messages into other OSC messages. We provide

examples of this strategy and show benefits including increased encapsulation

and program clarity.

Introduction

Shafqat Ali Kahn

Matt Wright (R)

Open Sound Control

An OSC Address Subspace for Wacom Tablet Data

/{tip, eraser}/{hovering, drawing} x y xtilt ytilt pressure

/{tip, eraser}/{touch, release} x y xtilt ytilt

/{airbrush, puckWheel, puckRotation} value

/buttons/[1-2] booleanValue

Wacom-OSC object outputs OSC messages with different addresses for the

different states. For example, if the eraser end of the pen is currently

touching the tablet, Wacom-OSC continuously outputs messages whose

address is /eraser/drawing and whose arguments are the current values of position, tilt, and pressure.

Wacom-OSC outputs the message /eraser/release. As long as the

eraser is within range of the tablet surface, Wacom-OSC continuously

outputs messages with the address /eraser/hovering and the same

position, tilt, and pressure arguments.Wacom-OSC, and hidden from

the interface designer. The interface designer simply uses the existing

mechanisms for routing OSC messages to map the different pen states to

different musical behaviors.Wacom-Regions takes the OSC messages

from Wacom-OSC and prepends the appropriate region name for events that

occur in the region. Wacom-OSC outputs the message /tip/drawing with

arguments giving the current pen position, tilt, and pressure.

Wacom-Regions looks up this current pen position in the data structure

of all the regions and sees that the pen is currently in region

foo so it outputs the message /foo/tip/drawing

with the same arguments. Now the standard OSC message routing mechanisms can

dispatch these messages to the part of the program that implements the

behavior of the region foo.

4. Dimensionality Reduction for the Tactex Control Surface

/area <area_of_inscribed_triangle>

/averageX <avg_X_value>

/averageY <avg_Y_value>

/incircle/radius <Incircle radius>

/incircle/area <Incircle area>

/sideLengths <side1> <side2> <side3>

/baseLength <length_of_longest_side>

/orientation <slope_of_longest_side>

/pressure/average <avg_pressure_value>

/pressure/max <maximum_pressure_value>

/pressure/min <minimum_pressure_value>

/pressure/tilt <leftmost_Z-rightmost_Z>

An OSC Address Space for Joysticks

/joystick/b xtilt

ytilt rotation/joystick/d xtilt

ytilt rotation/joystick/b

are then routed to the software implementing the behavior associated with

button B with the normal OSC message routing

mechanisms.Mapping Incoming MIDI to OSC

/footpedal1, so the

mapping of MIDI to synthesis control is clear and

self-documenting.Controller Remapping

OSC to Control Hexaphonic Guitar Processing

/3/tap2time sets the time of the

second delay tap for the third string. We can then leverage OSC’s

pattern-matching capabilities, for example,

by sending the message /[4-6]/tap[3-4]gain to set the gain of taps three

and four of strings four, five, and six all at once.Example: A Tactex-Controlled Granular Synthesis Instrument

Conclusion

References

Boie, B., M. Mathews, and A. Schloss 1989. The Radio Drum as a Synthesizer Controller. Proceedings of the International Computer Music Conference, Columbus, OH, pp. 42-45.

Buchla, D. 2001. Buchla Thunder. http://www.buchla.com/historical/thunder/index.html

Tactex. 2001. Tactex Controls Home Page. http://www.tactex.com

Wright, M. 1998. Implementation and Performance Issues with Open Sound Control. Proceedings of the International Computer Music Conference, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Wright, M. and A. Freed 1997. Open Sound Control: A New Protocol for Communicating with Sound Synthesizers. Proceedings of the International Computer Music Conference, Thessaloniki, Hellas, pp. 101-104.

Wright, M., D. Wessel, and A. Freed 1997. New Musical Control Structures from Standard Gestural Controllers. Proceedings of the International Computer Music Conference, Thessaloniki, Hellas.

FastTouch Open Source Arduino Library for Fast, Portable, Low Fidelity Capacitive Sensing

Sun, 04/22/2018 - 13:40 — AdrianFreedThe example code provided with the library uses the Arduino Tone library to sound pitches according to which pins are touched.

Notice that each call to the fast touch library implements a cycle of a relaxation oscillator.

I am indebted to Alice Giordani for exemplifying use of the library so well in this dreamcatcher:

Sound, Vibration, and Retroaction in Deformable Displays

Sat, 01/27/2018 - 12:34 — AdrianFreedIntroduction

Visual displays on deformable surfaces are compelling because they are easy to adapt to for the generation of users who have become heavily trained in ocularcentric, planar screen touch interactions since their invention in the mid 1980’s. Visual display is not the only form of output possible on deformable surfaces and for many applications will not turn out to be the best.

The two well-known problems with colocating deformation and image are:

We are exploring other sense modalities for deformable displays that avoid these problems and offer interesting affordances for display designers.

Sound is one of those modalities that is so obvious and pervasive that it may be easily overlooked. The state of the art in terms of human expressivity and interactivity in deformable displays is the Indian tabla drum. Good tabla players have sufficient control to be able play melodies on the surface using palm pressure to control pitch and their fingers to sound the drum with a wide variety of dynamics and timbral change. We are still very far from being able to sense or actuate a surface with sufficient precision in time and space to support the control musicians have over such surface interactions. The last musical instrument to be developed in the west with comparable control was the Clavichord. The keys of the clavichord couple the fingers to what become the movable bridges of multiple strings. Good clavichord players have a control of dynamic range that equal that of the piano in addition to pitch and timbral control – both impossible for the piano. The piano displaced use of the clavichord by being much louder and more suitable for the concert hall than the parlor.

HCI designers usually want more control over the mapping between input and output than a special purpose musical instrument provides. The insertion of digital computation and electrical transduction involves too many compromises to discuss fully here. We will instead focus on a few key challenges using the author’s work and examples from various collaborators.

Figure 1: the Tablo

The author’s “Tablo” is a controller designed to capture palm and finger gestures that a table player might use. Sound output is emitted from below the surface. An array of programmable lights provides visual feedback (analogous to the frets of a guitar) shining through the translucent conductive stretchable fabric. This fabric drapes over electrically resistive strips, lowering their resistance which then becomes a measure of displacement. Piezoresistive fabric segments around the annular base of the instrument are used to estimate pressure and provide a reference point to measure dynamic changes in displacement as an estimate of finger velocity.

Anna Flagg and Hannah-Perner Wilson have both adapted the two main piezoresistive pressure surface design patterns [2] to deformable applications using stretchable conductive and piezoresistive fabrics.

The basic construction is illustrated for Flagg’s “Cuddlebot” in figure 2.

Figure 2: Cuddlebot construction

The Cuddlebot is an affective robot that displays its “emotional” responses as sounds and vibration according to the nature of sensed interactions with its body surface.

Figure 3 shows Perner-Wilson’s robot skin. It uses a tubular adaptation of a basic fabric pressure multitouch design of Figure 4 [3]. Display in this case is retroaction in the form of motion of segments of the robot arm.

Figure 3: Robot Skin

Figure 4:Piezorestive Pressure Multitouch

Figure 5 shows the author’s most recent experiment towards capturing the responsiveness of hand drums [1]. From the display point of view it is interesting because the fabric sensing materials are built directly on the moving surface of loudspeaker drivers. This colocates sensing, audio and vibrotactile stimulation and leverages recent developments in control theory to make the coupled systems stable and also new sound transducers that have a flat and robust diaphragm.

Figure 5: Colocation

Discussion and Conclusion

Two major challenges persist in the engineering of the display systems presented: temporal and spatial resolution. The legacy from office automation applications of the 1980’s of low frame rates (30-60Hz) and low input data rates (<100Hz) persists and pervades in the implementation of desktop and mobile operating systems. New applications of these displays in gaming, music and other situations where tight multimodal integration is important require controlled latencies and sample rates better than 1kHz. We have shown that the sensing-data-rate problem can be finessed by translating the data into digital audio [4]. The spatial resolution issue is hard to solve currently without more reliable ways to connect the stretchable materials to the rigid materials supporting the electronics. One of the more promising approaches to this problem is to build the electronics with stretchable or bendable materials.

References

Publication Keywords

First Paper Fingerphone Prototype

Mon, 01/15/2018 - 16:18 — AdrianFreedPervasive Cameras: Making Sense of Many Angles using Radial Basis Function Interpolation and Salience Analysis

Mon, 01/15/2018 - 15:38 — AdrianFreedPervasive Cameras: Making Sense of Many Angles using Radial Basis Function Interpolation and Salients Analysis

Abstract. This paper describes situations which lend themselves to the use of numerous cameras and techniques for displaying many camera streams simultaneously. The focus here is on the role of the “director” in sorting out the onscreen content in an artistic and understandable manner. We describe techniques which we have employed in a system designed for capturing and displaying many video feeds incorporating automated and high level control of the composition on the screen.

1 A Hypothetical Cooking Show

A typical television cooking show might include a number of cameras capturing the action and techniques on stage from a variety of angles. If the TV chef were making salsa for example, cameras and crew might be setup by the sink to get a vegetable washing scene, over the cutting board to capture the cutting technique, next to a mixing bowl to show the finished salsa, and a few varying wider angle shots which can focus on the chef's face while he or she explains the process or on the kitchen scene as a whole. The director of such a show would then choose the series of angles that best visually describe the process and technique of making salsa. Now imagine trying to make a live cooking show presentation of the same recipe by oneself. Instead of a team of camera people, the prospective chef could simply setup a bunch of high quality and inexpensive webcams in these key positions in one's own kitchen to capture your process and banter from many angles. Along with the role of star, one must also act as director and compose these many angles into a cohesive and understandable narrative for the live audience.

Here we describe techniques for displaying many simultaneous video streams using automated and high level control of the cameras' positions and frame sizes on the screen allowing a solo director to compose many angles quickly, easily, and artistically.

2 Collage of Viewpoints

Cutting between multiple view points would possibly obscure one important aspect in favor of another. In the cooking show example, a picture in picture approach would allow the display of both a closeup of a tomato being chopped and the face of the chef describing his or her cutting technique. The multi angle approach is a powerful technique for understanding all of the action being captured in a scene as well as artistically compelling and greatly simplifies the work of the director of such a scene. The multi-camera setup lends itself to a collage of framed video streams on a single screen (fig. 1 shows an example of this multi-angle approach). We would like to avoid a security camera style display that would leave much of the screen filled with unimportant content, like a view of a sink not being used by anyone.

Figure 1: A shot focusing on the cilantro being washed

We focus attention on a single frame by making it larger than the surrounding frames or moving it closer to the center. The system is designed to take in a number of scaling factors (user-defined and automated) which multiply together to determine the final frame size and position. The user-defined scaling factor is set with a fader on each of the video channels. This is useful for setting initial level and biasing one frame over another in the overall mix. Setting and adjusting separate channels can be time consuming for the user, so we give a higher level of control to the user that facilitates scaling many video streams at once smoothly and quickly. CNMAT's (Center for New Music and Audio Technologies) rbfi (radial basis function interpolation) object for Max/MSP/Jitter allows the user to easily switch between preset arrangements, and also explore the infinite gradients in between these defined presets using interpolation[1]. rbfi lets the user place data points (presets in this case) anywhere in a 2 dimensional space and explore that space with a cursor. The weight of each preset is a power function of the distance from the cursor. For example, one preset point might enlarge all of the video frames on particular positions in the rooms, say by the kitchen island, so as the chef walks over the kitchen island, all of the cameras near the island enlarge and all of the other cameras shrink. Another preset might bias cameras focused on fruits. With rbfi, the user can slider the cursor to whichever preset best fits the current situation. With this simple, yet powerful high level of control, a user is able to compose the scene quickly and artistically, even while chopping onions.

Figure 2: A screenshot focusing

on the mango being chopped and

the mixing bowl

3 Automating Control

Another technique we employ is to automate the direction of the scene by analyzing the content of the individual frame and then resizing to maximize the area of the frame containing the most salient features. This approach makes for fluid and dynamic screen content which focuses on the action in the scene without any person needing to operate the controls. One such analysis measures the amount of motion which is quantified by taking a running average of the number of changed pixels between successive frames in one video stream. The most dynamic video stream would have the largest motion scaling factor while the others shrink from their relative lack of motion. Another analysis is detecting faces using the openCV library and then promoting video streams with faces in them. The multiplied combination of user-defined and automated weight adjustment determines each frames final size on the screen. Using these two automations with the cooking show example, if the chef looks up at the camera and starts chopping a tomato, the video streams that contain the chef's face and the tomato being chopped would be promoted to the largest frames in the scene while the other less important frames shrink to accommodate the two.

Figure 3: A screenshot of the

finished product and some

cleanup

Figure 3: A screenshot of the

finished product and some

cleanup

Positioning on the screen is also automated in this system. The frames are able to float anywhere on and off the screen while edge detection ensures that no frames overlap. The user sets the amount of a few different forces that are applied to the positions of the frames on the screen. One force propels all of the frame towards the center of the screen. Another force pushes the frames to rearrang their relative positions on the screen. No single influence dictates the exact positioning or size of any video frame; this is only determined by the complex interaction of all of these scaling factors and forces.

4 Telematic Example

Aside from a hypothetical self-made cooking show, a tested application of these techniques is in a telematic concert situation. The extensive use of webcams on the stage works well in a colocation concert where the audience might be in a remote location from the performers. Many angles on one scene gives the audience more of a tele-immersive experience. Audiences can also experience fine details like a performer's playing subtly inside the piano or a bassist's intricate fretboard work without having to be at the location or seated far from the stage. The potential issue is sorting out all of these video streams without overwhelming the viewer with content. This can be achieved without a large crew of videographers at each site, but with a single director dynamically resizing and rearranging the frames based on feel or cues as well as analysis of the video stream's content.

Figure 4: This is a view of a pianist from many angles which

would giving an audience a good understanding of the room

and all of the player's techniques inside the piano and on the

keyboard.

References

1. Freed, A., MacCallum, J., Schmeder, A., Wessel, D.: Visualizations and Interaction Strategies for Hybridization Interfaces. New Instruments for Musical Expression (2010)

Pervasive Cameras: Making Sense of Many Angles using Radial Basis Function Interpolation and Salience Analysis, , Pervasive 2011, 12/06/2011, San Francisco, CA, (2011)The Paper FingerPhone: a case study of Musical Instrument Redesign for Sustainability

Mon, 01/15/2018 - 15:38 — AdrianFreedCommentary proposed for NIME Reader

The fingerphone is my creative response to three umbridges: the waste and unsustainability of musical instrument manufacturing practices, the prevailing absence of long historical research to underwrite claims of newness in NIME community projects, and the timbral poverty of the singular, strident sawtooth wavefrom of the Stylophone – the point of departure for the fingerphone instrument design.

This paper is the first at NIME of my ongoing provocations to the community to enlarge what we may mean by “new” and “musical expression”. I propose a change of scale away from solipsistic narratives of instrument builders and players to cummunitarian accounts that celebrate plural agencies and mediations [Born]. The opening gesture in this direction is a brief historicization of the fingerphone instrument. Avoiding the conventional trope of just differentiating this instrument from its immediate predecessors to establish “newness”, the fingerphone is enjoined to two rich instrumental traditions, the histories of which are still largely unwritten: stylus instruments, and electrosomatophones. The potential size of this iceberg is signaled by citing a rarely-cited musical stylus project from 1946 instead of the usually cited projects of the 1970’s, e.g. Xanakis’s UPIC or the Fairlight CMI lightpen.

Electrosomatophones are electronic sounding instruments that integrate people’s bodies into their circuits. They are clearly attested in depictions from the eighteenth century of Stephen Gray’s “flying boy” experiments and demonstrations, where a bell is rung by electrostatic forces produced by electric charges stored in the body of a boy suspended in silks. Electrosomatophones appear regularly in the historical record from this period to the present day.

The production of Lee De Forest’s audion tube is an important disruptive moment because the vacuum tube provided amplification and electrical isolation permitting loud sounds to be emitted from electrosomatophones without the pain of correspondingly large currents running through the performer’s body. While the theremin is the electrosomatophone that has gained the most social traction, massification of electrosomatophone use began with the integration of capacitive multitouch sensing into cellphones–an innovation prefigured by Bill Buxton [Buxton] and Bob Boie’s [radio drum] inventions of the mid-1980’s.

Achieving the sustainable design properties of the fingerphone required working against the grain of much NIME practice, especially the idea of separating controller, synthesizer and loudspeaker into their own enclosures. Such a separation might have been economical at a time when enclosures, connectors and cables were cheaper than the electronic components they house and connect but now the opposite is true. Instead of assembling a large number of cheap, specialized monofunctional components, the fingerphone uses a plurifuctional design approach where materials are chosen, shaped and interfaced to serve many functions concurrently. The paper components of the fingerphone serve as interacting surface, medium for inscription of fiducials, sounding board and substrate for the electronics. The first prototype fingerphone was built into a recycled pizza box. The version presented at the NIME conference was integrated into the poster used for the presentation itself. This continues a practice I initially using e-textiles for, the practice of choosing materials that give design freedoms of scale and shape instead of using rigid circuit boards and off-the-shelf sensors. This approach will continue to flourish and become more commonplace as printing techniques for organic semiconductors, sensors and batteries are massified.

The fingerphone has influenced work on printed loudspeakers by Jess Rowland and the sonification of compost by Noe Parker. Printed keyboards and speakers are now a standard application promoted by manufacturers of conductive and resistive inks.

In addition to providing builders with an interesting instrument design, I hope the fingerphone work will lead more instrument builders and players to explore the nascent field of critical organology, deepen discourse of axiological concerns in musical instrument design, and adduce early sustainability practices that ecomusicologists will be able to study.

The Paper FingerPhone: a case study of Musical Instrument Redesign for Sustainability

Adrian Freed

Introduction

Stylophone

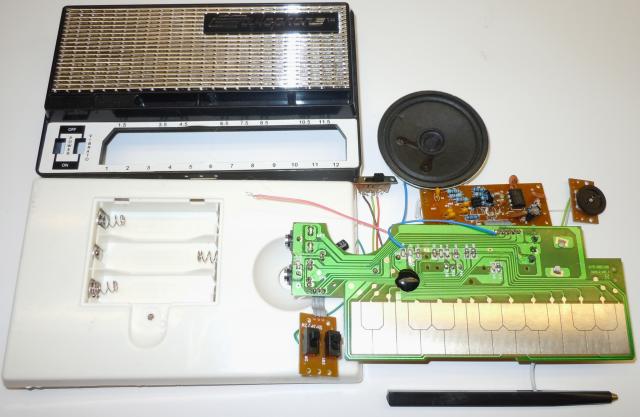

The Stylophone is a portable electronic musical instrument that was commercialized in the 1970's and enjoyed a brief success primarily in the UK. This is largely attributable to its introduction on TV by Rolf Harris, its use in the song that launched David Bowie's career, "Space Oddity," and its appearance in a popular TV series "The Avengers". Three million instruments were sold by 1975. A generation later the product was relaunched. The artist "Little Boots" has prompted renewed interest in the product by showcasing it in her hit recording "Meddle".

Mottainai! (What a waste!)

The Stylophone in its current incarnation is wasteful in both its production and interaction design. The new edition has a surprisingly high parts count, material use and carbon footprint. The limited affordances of the instrument waste the efforts of most who try to learn to use it.

Musical toy designers evaluate their products according to MTTC (Mean Time to Closet), and by how many battery changes consumers perform before putting the instrument aside [1]. Some of these closeted instruments reemerge a generation later when "old" becomes the new "new"-but most are thrown away.

This paper addresses both aspects of this waste by exploring a rethinking and redesign of the Stylophone, embodied in a new instrument called the Fingerphone.

1.3 History

The Stylophone was not the first stylus-based musical instrument. Professor Robert Watson of the University of Texas built an “electric pencil” in 1948 [2]. The key elements for a wireless stylus instrument are also present in the David Grimes patent of 1931 [3] including conductive paper and signal synthesis from position-sensing potentiometers in the pivots of the arms of a pantograph. Wireless surface sensing like this wasn’t employed commercially until the GTCO Calcomp Interwrite’s Schoolpad of 1981.

Electronic

musical instruments like the Fingerphone with unencumbered surface interaction

were built as long ago as 1748 with the Denis d’Or of Václav Prokop

Diviš.

Interest in and development of such instruments continued with those of Elisha Gray

in the late 1800’s, Theremin in the early 1900’s, Eremeeff, Trautwein, Lertes,

Heller in the 1930’s, Le Caine in the 1950’s, Michel Waisvisz and Don Buchla in the

1960’s, Salvatori Martirano and the circuit benders in the 1970’s [4].

1.4 Contributions

The basic sensing principle, sound synthesis method and playing style of the Stylophone and Fingerphone are well known so the novel aspects of the work presented here are in the domain of the tools, materials, form and design methods with which these instruments are realized.

Contributions of the paper include: a complete musical instrument design that exploits the potential of paper sensors, a novel strip origami pressure sensor, surface e-field sensing without external passive components, a new manual layout to explore sliding finger gestures, and suggestions of how to integrate questions of sustainability and longevity into musical instrument design and construction.

2. The Fingerphone

2.1 Reduce

The Fingerphone (Figure 2) achieves low total material use, low energy cost and a small carbon footprint by using comparatively thin materials, recycled cellulose and carbon to implement the functions of the Stylophone without its high-energy cost and toxic materials: plastics, metals, glass fiber and resins.

Figure 2: The Fingerphone

The Stylophone contains two major, separate circuit boards with a different integrated circuit on each: one for the oscillator and stylus-board, the other for an LM386 power amplifier for the small speaker. The Fingerphone has only one integrated circuit, an Atmel 8-bit micro-controller, that is used to sense e-field touch and pressure on paper transducers, synthesize several digital oscillators and drive the sound transducer using an integrated pulse width modulation controller (PWM) as an energy-efficient, inductor-less class D amplifier.

The Fingerphone’s playing surface, switches and volume control functions are achieved using conductive paper [5, 6]. Various other materials were explored including embroidered silver plaited nylon thread (Figure 3), and a water-based silk-screened carbon-loaded ink (Figure 4).

Figure 3:

Embroidered Manual

Figure 4: Printed Manual

Paper is an interesting choice because cellulose, its core component, is the most common polymer, one that can be harvested sustainably and is also readily available as a recycled product.

Complete carbon footprint, and lifecycle cost analyses are notoriously hard to do well but we can use some simple measures as proxies: The Stylophone has 65 components, a production Fingerphone would have only six. Manufacturing process temperature is another useful proxy: the Stylophone’s metals, plastic and solder suggest a much higher cost than those associated with paper. At first glance it would appear that the waste stream from the paper of the Fingerphone might be more expensive than the Stylophone. In fact they are similar because of the packaging of the reels the surface mount parts are contained in during manufacturing of the Stylophone. The Fingerphone waste paper stream can be recycled back into future Fingerphones.

In some products, such as grocery bags, plastic compares favorably to paper in terms of environmental impact and production energy budgets. Paper has the advantage in musical instrument s such as the Fingerphone of providing a medium to inscribe multiple functions—a plurifunctionality difficult to achieve with plastics or metals. These functions include: visual and tactile fiducials for the performer, highly conductive and insulating regions for the playing surface, a membrane for the bending wave sound transducer and an absorbent and thermally insulating substrate for connections and support of the micro-controller and output transducer. This plurifunctionality is found in traditional fretted chordophones: frets serve as fiducials, to define the length of the sounding string, as a fulcrum for tension modulation of the string and as an anvil to transfer energy to the string in the "hammer on" gesture.

Capacitive sensing of the performer's digits obviates the need for the Stylophone's metal wand and connecting wire entirely. Employing a distributed-mode driver eliminates the need for a loudspeaker cone and metal frame. In this way the entire instrument surface can be used as an efficient radiator.

The prototype of Figure 2 uses a small, readily available printed circuit board for the Atmel micro-controller; the production version would instead use the common "chip on board" technique observable as a black patch of epoxy on the Stylophone oscillator board, on cheap calculators and other high volume consumer products. This technique has been successfully used already for paper and fiber substrates as in Figure 5 [7].

Figure 5: Chip on Fabric

In conventional electronic design the cost of simple parts such as resistors and capacitors is considered to be negligible; laptop computers, for example, employ hundreds of these discrete surface mounted parts. This traditional engineering focus on acquisition cost from high volume manufacturers doesn’t include the lifecycle costs and, in particular, ignores the impact of using such parts on the ability for users to eventually recycle or dispose of the devices. Rather than use a conventional cost rationale the Fingerphone design was driven by the question: how can each of these discrete components be eliminated entirely? For example, Atmel provides a software library and guide for capacitance sensing. Their design uses a discrete resistor and capacitor for each sensor channel. The Fingerphone uses no external resistors or capacitors. The built-in pull-up resistors of each I/O pin are used instead in conjunction with the ambient capacitance measured between each key and its surrounding keys.

The Stylophone has a switch to engage a fixed frequency and fixed depth vibrato, and rotary potentiometers to adjust pitch and volume. These functions are controlled on the Fingerphone using an origami piezoresistive sensor and linear paper potentiometers. The former is a folded strip of paper using a flattened thumb knot that forms a pentagon (Figure 6). Notice that 3 connections are made to this structure eliminating the need for a pull up resistor and establishing a ratiometric measure of applied pressure.

Figure 6: Origami Force Sensor

The remaining discrete components on the micro-controller board can be eliminated in a production version: The LED and its series resistor are used for debugging—a function easily replaced using sound [8]. The micro-controller can be configured to not require either a pull-up resistor or reset button and to use an internal RC clock instead of an external crystal or ceramic resonator. This RC clock is not as accurate as the usual alternatives but certainly is as stable as the Stylophone oscillator. This leaves just the micro-controller’s decoupling capacitor.

The magnet of the sound transducer shown in Figure 2 is one of the highest energy-cost devices in the design. A production version would use a piezo/ceramic transducer instead. These have the advantage of being relatively thin (1-4mm) and are now commonly used in cellphones and similar portable devices because they don't create magnetic fields that might interfere with the compasses now used in portable electronics. By controlling the shape of the conductive paper connections to a piezo/ceramic transducer a low-pass filter can be tuned to attenuate high frequency aliasing noise from the class D amplifier.

Reuse

Instead of the dedicated battery compartment of the Stylophone, the Fingerphone has a USB mini connector so that an external, reusable source of power can be connected — one that is likely to be shared among several devices, e.g, cameras, cellphones, or laptop computers. Rechargable, emergency chargers for cellphones that use rechargeable lithium batteries and a charging circuit are a good alternative to a disposable battery (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Reusable Power Sources

This approach of providing modular power sources shared between multiple devices may be found in modern power tool rechargeable battery packs, and in the Home Motor of 1916. This was available from the Sears mail order catalog with attachments for sewing, buffing, grinding, and sexual stimulation [9].

The Fingerphone components are installed on a light, stiff substrate to provide a resonating surface for the bending mode transducers. This has been found to be a good opportunity for reuse so prototype Fingerphones have been built on the lid of a pizza box, a cigar box, and a sonic greeting card from Hallmark - all of which would normally be discarded after their first use. Such reuse has precedent in musical-instrument building, e.g., the cajon (cod-fish shipping crates), the steel-pan (oil drums), and ukulele (cigar boxes).

2.3 Recycle

The bulk of the Fingerphone is recyclable, compostable paper. A ring of perforations in the paper around the micro-controller would facilitate separation of the small non-recyclable component from the recyclable paper.

Use Maximization

Introduction

The Stylophone has a single, strident, sawtooth-wave timbre. There is no control over the amplitude envelope of the sawtooth wave other than to turn it off. This guarantees (as with the kazoo, harmonica, and vuvuzela) that the instrument will be noticed - an important aspect of the gift exchange ritual usually associated with the instrument. This combination of a constrained timbre and dynamic envelope presents interesting orchestration challenges. These have been addressed by David Bowie and Little Boots in different ways: In early recordings of "Space Oddity" the Stylophone is mostly masked by rich orchestrations--in much the way the string section of an orchestra balances the more strident woodwinds such as the oboe. Little Boots’ "Meddle" begins by announcing the song's core ostinato figure, the hocketing of four staccato "call" notes on the Stylophone with "responding" licks played on the piano. The lengths of call and response are carefully balanced so that the relatively mellow instrument, the piano, is given more time than the Stylophone.

3.2 Timbre

The oscillators of the Fingerphone compute a digital phasor using 24-bit arithmetic and index tables that include sine and triangle waves. The phasor can also be output directly or appropriately clipped to yield approximations to sawtooth and square/pulse waves respectively. Sufficient memory is available for custom waveshapes or granular synthesis. The result is greater pitch precision and more timbral options than the Stylophone.

Dynamics

An envelope function, shaped according to the touch expressivity afforded by electric field sensing, modulates the oscillator outputs of the Fingerphone. The level of dynamic control achieved is comparable to the nine "waterfall" key contacts of the Hammond B3 organ.

Legato playing is an important musical function and it requires control of note dynamics. The audible on/off clicks of the Stylophone disrupt legato to such an extent that the primary technique for melodic playing of the instrument is to rapidly slide the stylus over the keys to create a perceived blurring between melody notes. The dedicated performer with a steady hand can exploit a narrow horizontal path half way down the Stylophone stylus-board to achieve a chromatic run rather than the easier diatonic run

Legato in the Fingerphone is facilitated by duophony so that notes can actually overlap--as in traditional keyboard performance. Full, multi-voice polyphony is also possible with a faster micro-controller or by taking advantage of remote synthesis resources driven by the OSC and MIDI streams flowing from the Fingerphone’s USB port.

Manual Layouts

Figure 8: Trills

Surface interaction interfaces provide fundamentally different affordances to those of sprung or weighted action keyboards. In particular it is slower and harder to control release gestures on surfaces because they don’t provide the stored energy of a key to accelerate and preload the release gesture. This factor and the ease of experimentation with paper suggest a fruitful design space to explore: new surface layout designs. The layout illustrated in Figure 4 resulted from experiments with elliptical surface sliding gestures that were inspired by the way Dobro and lapstyle guitar players perform vibrato and trills. Various diatonic and chromatic ascending, descending and cyclical runs and trills can be performed by orienting, positioning and scaling these elliptical and back and forth sliding gestures on the surface.

3.5 Size Matters

By scaling the layout to comfortable finger size it is possible to play the white “keys" between the black ones-something that is impossible with the Stylophone layout.

The interesting thing about modulations of size in interactive systems is that continuous changes are experienced as qualitatively discrete, i.e., For each performer, certain layouts become too small to reliably play or too large to efficiently play. The economics of mass manufacturing interacts with this in a way that historically has narrowed the number of sizes of instruments that are made available. For example, the Jaranas of the Jarochos of Mexico are a chordophone that players build for themselves and their children. They are made “to measure” with extended families typically using seven or eight different sizes. The vast majority of manufactured guitars on the other hand are almost entirely “full size” with a few smaller sizes available for certain styles. This contrasting situation was also present with the hand-built fretless banjos of the 19th century now displaced by a few sizes of manufactured, fretted banjos.

In the case of the Stylophone the NRE (Non-recurring Engineering) costs for two molds and the circuit boards discourage the development of a range of sizes. There are also costs associated with the distribution and shelving in stores of different sizes. The lower cost structures of the Fingerphone on the other hand allow for a wider range of sizes. Prototypes have been developed by hand and with a cheap desktop plotter/cutter. Different scales can be experimented with in minutes instead of the hours required to develop circuit boards. Also, die cutting of paper is cheaper than injection molding or etching in production.

The use of a finger-size scale would appear to put the Fingerphone at a portability disadvantage with respect to the Stylophone. It turns out that fabric and paper allow for folded Fingerphones that are no larger than the Stylophone for transport. Roll-up computer keyboards and digitizing tablets are precedents for this approach.

Discussion

Impact

By itself the Fingerphone will not have a significant direct impact on the sustainability issues the world faces. However, now that musical instrument building is being integrated as standard exercises in design school classes, the Fingerphone can serve as a strong signal that more environmentally responsible materials and design techniques are available.

Design Theory

Simondon’s thesis on the technical object [0] describes the value of plurifunctionality to avoid the pitfalls of “hypertelic and maladapted designs”. Judging by the number of huge catalogs of millions of highly functionally-specific electronic parts now available, the implications of Simondon’s philosophical study were largely ignored. The Fingerphone illustrates how plurifunctionality provides designers with an alternative route to economies of scale than the usual high-volume-manufacturing one where the cost of development is amortized over a large number of inscribed functions instead of a large number of high volume parts.

Transitional Instruments

The Fingerphone adds to a debate in the NIME community about accessibility, ease of use and virtuosity. Wessel and Wright declare that it is possible to build instruments with a low entry point and no ceiling on virtuosity [11]. Blaine and Fels argue that this consideration is irrelevant to casual users of collaborative instruments [12]. Isn’t there a neglected space in between of transitional instruments that serve people on a journey as they acquire musical skills and experience? Acoustic instrument examples include the melodica, ukulele and recorder. The Stylophone, in common with Guitar hero and Paper Jamz, is designed with a primary focus on social signaling of musical performance. The Fingerphone shows that affordable instruments may be designed that both call attention to the performer and also afford the exercise and development of musical skills, and a facilitated transition to other instruments.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks for support from Pixar/Disney, Meyer Sound Labs, Nathalie Dumont from the Concordia University School of Fine Arts and the Canada Grand project.

REFERENCES

[1] S.

Capps, "Toy Musical Instrument Design,", Personal Communication, Menlo Park, 2011.

[8] A.

Turing, Manual for the Ferranti Mk. I:

University of Manchester, 1951.

[10] G.

Simondon, Du mode d'existence des objets

techniques. Paris: Aubier-Montaigne, 1958.

Wearable Video Game Platform Bracelet

Mon, 06/21/2010 - 13:45 — AdrianFreedHow many interactions/games can you think of with this platform?

There are 3 in the video:

Hand in the air: flashes (because at a party you want to signal that you want someone to talk to?).

Horizontal hand: always illuminates the top LED's whatever rotation your arm has ("smart flashlight")

Spins of the wrist: a blob spins around in the same direction and slows to a stop.

For a commercially produced inertial-sensing band keep an eye out on getymyo