This annotated version by Adrian Freed borrows some ideas from medieval glosses. It is intented to provide context and readability unavailable in the original pdf.

ICMC

Managing Complexity with Explicit Mapping of Gestures to Sound Control with OSC

Fri, 03/12/2021 - 13:32 — AdrianFreedManaging Complexity

with Explicit Mapping of Gestures to Sound Control

with OSC

Matthew Wright

Adrian Freed

Ahm Lee

Tim Madden

Ali Momeni

email: {matt,adrian,ahm,tjmadden,ali}@cnmat.berkeley.edu

Open Sound Control (OSC) offers much to the

creators of these gesture-to-sound-control mappings: It is general enough to

represent both the sensed gestures from physical controllers and the parameter

settings needed to control sound synthesis. It provides a uniform syntax

and conceptual framework for this mapping. The symbolic names for all OSC

parameters make explicit what is being controlled and can make programs easier

to read and understand. An OSC interface to a gestural-sensing or

signal-processing subprogram is an effective form of abstraction that exposes

pertinent features while hiding the complexities of implementation.

We present a paradigm for using OSC for mapping tasks and describe a

series of examples culled from several years of live performance with a

variety of gestural controllers and performance paradigms.

Open Sound Control (OSC) was originally developed to facilitate the

distribution of control-structure computations to small arrays of loosely-coupled heterogeneous computer systems.

A common application of OSC is to

communicate control-structure computations from one client machine to an array

of synthesis servers. The abstraction mechanisms built into OSC, a

hierarchical name space and regular-expression message dispatch, are also useful

in implementations running entirely on a single

machine. In this situation we have adapted the OSC client/server model to the organization of the gestural

component of control-structure computations.

The basic strategy is to:

Now the gestural performance mapping is simply a translation of one set of

OSC messages to another. This gives performers greater scope and facility in

choosing how best to effect the required parameter changes.

Wacom digitizing graphic tablets are attractive gestural interfaces for

real-time computer music. They provide extremely accurate two-dimensional

absolute position sensing of a stylus, along with measurements of pressure,

two-dimensional tilt, and the state of the switches on the side of the stylus,

with reasonably low latency. The styli (pens) are two-sided, with a

tip and an eraser.;

The tablets also support other

devices, including a mouse-like puck, and can be used with two

devices simultaneously.

Unfortunately, this measurement data comes from the Wacom drivers in an inconvenient form. Each

of the five continuous parameters is available independently, but another parameter,

the device type, indicates what kind of device is being used and,

for the case of pens, whether the tip or eraser is being used. For a program to

have different behavior based on which end of the pen is used, there must be a

switching and gating mechanism to route the continuous parameters to the correct

processing based on the device type. Similarly, the tablet senses

position and tilt even when the pen is not touching the tablet, so a program that

behaves differently based on whether or not the pen is touching the tablet must

examine another variable to properly dispatch the continuous parameters. Instead of simply providing the raw data from the Wacom drivers, our

At the moment the eraser end of the pen is released from the tablet,

With this scheme, all of the dispatching on the device type

variables is done once and for all inside We use another level of OSC addressing to define

distinct behaviors for different regions of the tablet. The interface designer

creates a data structure giving the names and locations of any number of regions

on the tablet surface. An object called For example, suppose the pen is drawing within a region named

foo. Once again tedious programming work is hidden from the interface designer,

whose job is simply to take OSC messages describing tablet gestures and map

them to musical control. Tactex's MTC Express controller senses pressure at multiple points on

a surface. The primary challenge using the device is to reduce the high

dimensionality of the raw sensor output (over a hundred pressure values) to a

small number of parameters that can be reliably controlled. One approach is to install physical

tactile guides over the surface and interpret the result as a set of sliders controlled

by a performer's fingers. Apart from not fully exploiting the potential of

the controller this approach has the disadvantage of introducing delays as the

performer finds the slider positions. An alternative approach

is to interpret the output of the tactile array as an image and use

computer vision techniques to estimate pressure for each finger of the hand. Software

provided by Tactex outputs four parameters for each of up to five sensed fingers,

which we represent with the following OSC addresses:

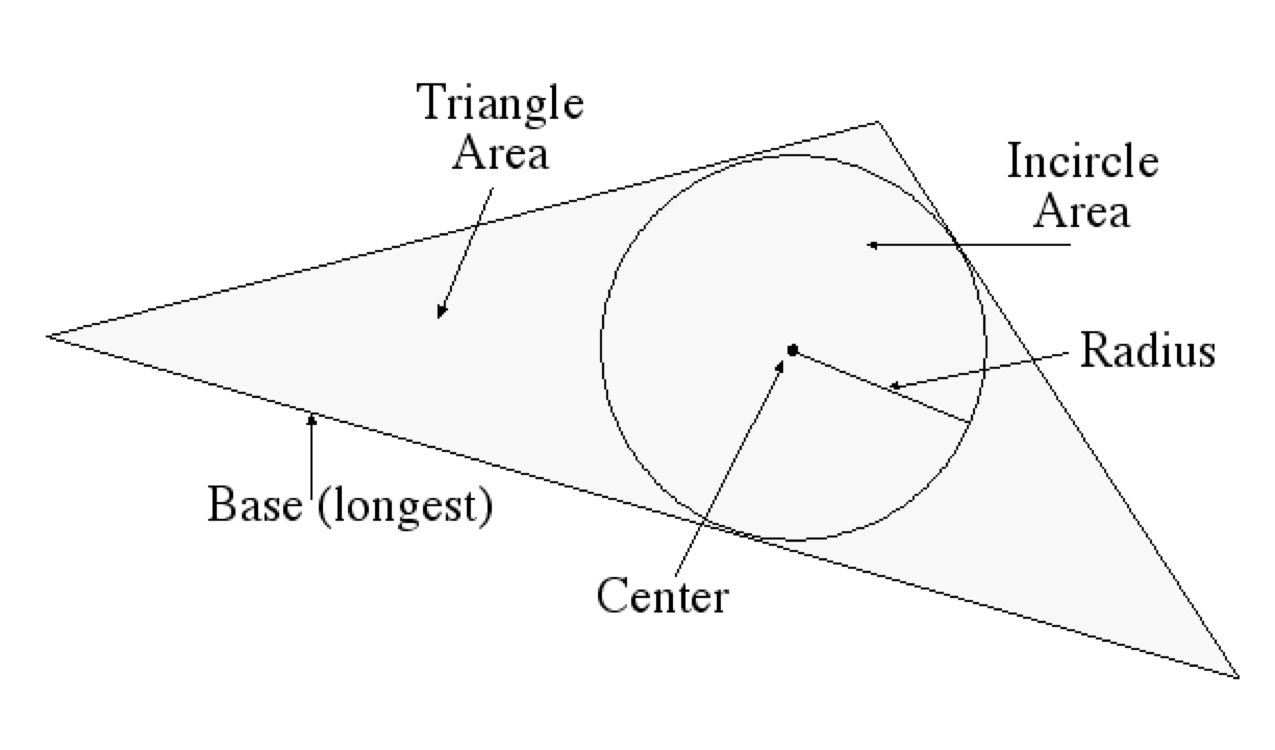

The anatomy of the human hand makes it impossible to control these four

variables independently for each of five fingers. We have developed another

level of analysis, based on interpreting the parameters of three fingers as a

triangle, as shown below. This results in the parameters listed below.

These parameters are particularly easy to control and were chosen because they work

with any orientation of the hand. USB joysticks used for computer games also have good properties as musical

controllers. One model senses two dimensions of tilt, rotation of the

joystick, and a large array of buttons and switches. The buttons support

chording, meaning that multiple buttons can be pressed at once and

detected individually. We developed a modal interface in which each button corresponds to a particular musical

behavior. With no buttons pressed, no sound results. When one or more buttons

are pressed, the joystick's tilt and rotation continuously affect the behaviors

associated with those buttons. The raw joystick data is converted into OSC messages whose address

indicates which button is pressed and whose arguments give the current

continuous measurements of the joystick’s state. When two or more buttons

are depressed, the mapper outputs one OSC message per depressed button, each

having identical arguments. For example, while buttons B and

D are pressed, our software continuously outputs these two

messages: Messages with the address Suppose a computer-music instrument is to be controlled by two keyboards,

two continuous foot-pedals, and a foot- switch. There is no reason for the

designer of this instrument to think about which MIDI channels will be used,

which MIDI controller numbers the foot-pedals output, whether the input comes

to the computer on one or more MIDI ports, etc. We map MIDI message to OSC messages as soon as possible. Only the part of

the program which does this translation needs to embody any of the MIDI

addressing details listed above. The rest of the program sees messages with

symbolic names like The use of an explicit mapping from gestural input to sound control, both

represented as OSC messages, makes it easy to change this mapping in real-time

to create different modes of behavior for an instrument. Simply route incoming

OSC messages to the mapping software corresponding to the current mode. For example, we have developed Wacom tablet interfaces where the region in

which the pen touches the tablet surface defines a musical behavior to be

controlled by the continuous pen parameters even as the pen moves outside the

original region. Selection of a region when the pen touches the tablet

determines which mapper(s) will interpret the continuous pen parameters until

the pen is released from the tablet. We have created a large body of signal processing instruments that

transform the hexaphonic output of an electric guitar. Many of these effects

are structured as groups of 6 signal-processing modules, one for each string,

with individual control of all parameters on a per-string basis. For example,

a hexaphonic 4-tap delay has 6 signal inputs, 6 signal outputs, and six groups

of nine parameters: the gain of the undelayed signal, four tap times, and

four tap gains. OSC gives us a clean way to organize these 54 parameters. We make an

address space whose top level chooses one of the six delay lines with the

numerals 1-6, and whose bottom level names the parameters. For example, the

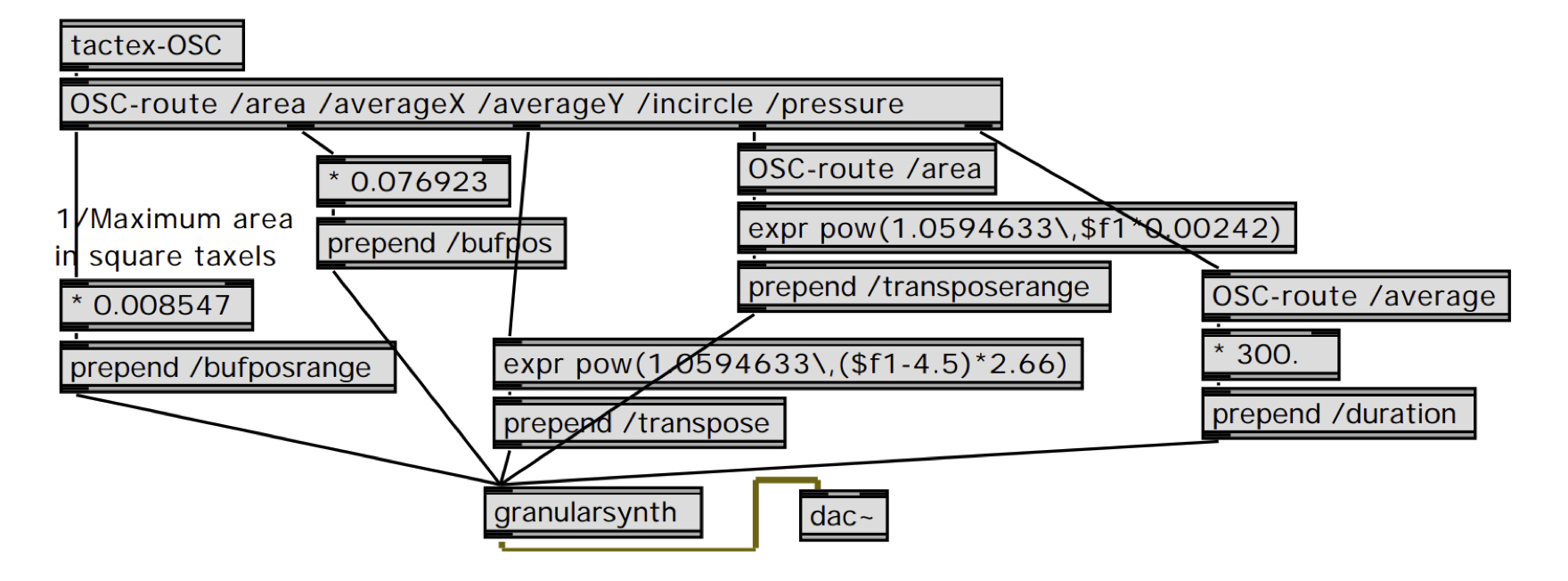

address We have developed an interface that controls granular synthesis from the

triangle-detection software for the Tactex MTC described above. Our granular

synthesis instrument continuously synthesizes grains each with a location in

the original sound and frequency transposition value that are chosen randomly

from within a range of possible values. The real-time-controllable parameters

of this instrument are arranged in a straightforward OSC address

space: The Max/MSP patch shown below maps incoming Tactex

triangle-detection OSC messages to OSC messages to control this granular

synthesizer.

This mapping was codeveloped with Guitarist/Composer John Schott and used

for his composition The Fly.

We have described the benefits in diverse contexts of explicit mapping of

gestures to sound control parameters with OSC.

UC Berkeley

1750 Arch St.

Berkeley, CA 94709, USA

Abstract

We present a novel use of the OSC protocol to represent the output

of gestural controllers as well as the input to sound synthesis processes. With

this scheme, the problem of mapping gestural input into sound synthesis control

becomes a simple translation from OSC messages into other OSC messages. We provide

examples of this strategy and show benefits including increased encapsulation

and program clarity.

Introduction

Shafqat Ali Kahn

Matt Wright (R)

Open Sound Control

An OSC Address Subspace for Wacom Tablet Data

/{tip, eraser}/{hovering, drawing} x y xtilt ytilt pressure

/{tip, eraser}/{touch, release} x y xtilt ytilt

/{airbrush, puckWheel, puckRotation} value

/buttons/[1-2] booleanValue

Wacom-OSC object outputs OSC messages with different addresses for the

different states. For example, if the eraser end of the pen is currently

touching the tablet, Wacom-OSC continuously outputs messages whose

address is /eraser/drawing and whose arguments are the current values of position, tilt, and pressure.

Wacom-OSC outputs the message /eraser/release. As long as the

eraser is within range of the tablet surface, Wacom-OSC continuously

outputs messages with the address /eraser/hovering and the same

position, tilt, and pressure arguments.Wacom-OSC, and hidden from

the interface designer. The interface designer simply uses the existing

mechanisms for routing OSC messages to map the different pen states to

different musical behaviors.Wacom-Regions takes the OSC messages

from Wacom-OSC and prepends the appropriate region name for events that

occur in the region. Wacom-OSC outputs the message /tip/drawing with

arguments giving the current pen position, tilt, and pressure.

Wacom-Regions looks up this current pen position in the data structure

of all the regions and sees that the pen is currently in region

foo so it outputs the message /foo/tip/drawing

with the same arguments. Now the standard OSC message routing mechanisms can

dispatch these messages to the part of the program that implements the

behavior of the region foo.

4. Dimensionality Reduction for the Tactex Control Surface

/area <area_of_inscribed_triangle>

/averageX <avg_X_value>

/averageY <avg_Y_value>

/incircle/radius <Incircle radius>

/incircle/area <Incircle area>

/sideLengths <side1> <side2> <side3>

/baseLength <length_of_longest_side>

/orientation <slope_of_longest_side>

/pressure/average <avg_pressure_value>

/pressure/max <maximum_pressure_value>

/pressure/min <minimum_pressure_value>

/pressure/tilt <leftmost_Z-rightmost_Z>

An OSC Address Space for Joysticks

/joystick/b xtilt

ytilt rotation/joystick/d xtilt

ytilt rotation/joystick/b

are then routed to the software implementing the behavior associated with

button B with the normal OSC message routing

mechanisms.Mapping Incoming MIDI to OSC

/footpedal1, so the

mapping of MIDI to synthesis control is clear and

self-documenting.Controller Remapping

OSC to Control Hexaphonic Guitar Processing

/3/tap2time sets the time of the

second delay tap for the third string. We can then leverage OSC’s

pattern-matching capabilities, for example,

by sending the message /[4-6]/tap[3-4]gain to set the gain of taps three

and four of strings four, five, and six all at once.Example: A Tactex-Controlled Granular Synthesis Instrument

Conclusion

References

Boie, B., M. Mathews, and A. Schloss 1989. The Radio Drum as a Synthesizer Controller. Proceedings of the International Computer Music Conference, Columbus, OH, pp. 42-45.

Buchla, D. 2001. Buchla Thunder. http://www.buchla.com/historical/thunder/index.html

Tactex. 2001. Tactex Controls Home Page. http://www.tactex.com

Wright, M. 1998. Implementation and Performance Issues with Open Sound Control. Proceedings of the International Computer Music Conference, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Wright, M. and A. Freed 1997. Open Sound Control: A New Protocol for Communicating with Sound Synthesizers. Proceedings of the International Computer Music Conference, Thessaloniki, Hellas, pp. 101-104.

Wright, M., D. Wessel, and A. Freed 1997. New Musical Control Structures from Standard Gestural Controllers. Proceedings of the International Computer Music Conference, Thessaloniki, Hellas.

I almost killed Bob Moog

Tue, 05/07/2019 - 09:10 — AdrianFreedDynamic, Instance-based, Object-Oriented Programming (OOP) in Max/MSP using Open Sound Control (OSC) Message Delegation

Mon, 01/15/2018 - 14:38 — AdrianFreedo.io: a Unified Communications Framework for Music, Intermedia and Cloud Interaction

Mon, 01/15/2018 - 14:38 — AdrianFreedPublication Keywords

Dynamic Message-Oriented Middleware with Open Sound Control and Odot

Mon, 01/15/2018 - 14:38 — AdrianFreedOpen Sound Control: A New Protocol for Communicating with Sound Synthesizers

Mon, 09/21/2009 - 10:57 — AdrianFreed1 Introduction

A better integration of computers, controllers and sound synthesizers will lead to lower costs, increased reliability, greater user convenience, and more reactive musical control. The prevailing technologies to interconnect these elements are bus (motherboard or PCI), operating system interface (software synthesis), or serial LAN (Firewire, USB, ethernet, fast ethernet). It is easy to adapt MIDI streams to this new communication substrate [11]. To do so needlessly discards new potential and perpetuates MIDI's well-documented flaws. Instead we have designed a new protocol optimized for modern transport technologies.

Open SoundControl is an open, efficient, transport-independent, message-based protocol developed for communication among computers, sound synthesizers, and other multimedia devices. Open SoundControl is a machine and operating system neutral protocol and readily implementable on constrained, embedded systems.

We begin by examining various networking technologies suitable for carrying Open SoundControl data and discuss shared features of these technologies that impact the design of our protocol. Next we discuss the encoding and formatting of data. We describe our novel addressing scheme based on a URL-style symbolic syntax. In our last section we specify a number of query messages that request information from an Open SoundControl system.

2 Transport Layer Assumptions

Open SoundControl is a transport-independent protocol, meaning that it is a format for data that can be carried across a variety of networking technologies. Networking technologies currently becoming widely available and economical include high speed busses such as PCI [8] and medium speed serial LANs such as USB [10], IEEE-1394 ("Firewire") [3], Ethernet, and Fast Ethernet [4]. Although Open SoundControl was not designed with a particular transport layer in mind, our design reflects features shared by modern networking technologies.

We assume that Open SoundControl will be transmitted on a system with a bandwidth in the 10+ megabit/sec range. MIDI's bandwidth, by contrast, is only 31.25 kilobit/sec, roughly 300 times slower. Therefore, our design is not preoccupied with squeezing musical information into the minimum number of bytes. We encode numeric data in 32-bit or 64-bit quantities, provide symbolic addressing, time-tag messages, and in general are much more liberal about using bandwidth for important features.

We assume that data will be delivered in packets (a.k.a. "datagrams") rather than as a stream of data traveling along an established connection. (Although many LANs transmit data serially, they deliver the data as a single block.) This leads to a protocol that is as stateless as possible: rather than assuming that the receiver holds some state from previous communications (e.g., MIDI's running status), we send information in larger, self-contained chunks that include all the relevant data in one place. This packet-based delivery model provides a mechanism for synchronicity: messages in the same packet (e.g., messages to start each of the notes in a chord) can be specified to have their effects occur at the same time as each other. We assume that the network services will tell us the length of each packet that we receive.

All modern networking technologies have the notion of multiple devices connected together in a LAN, with each device able to send a packet to any other device. So we assume that any number of clients might send Open SoundControl messages to a particular device. We also assume that the transport layer provides a return address mechanism that allows a device to send a response back to the device that sends it a message.

3 Data Representation

All Open SoundControl data is aligned on 4-byte boundaries. Numeric data are encoded using native machine representations of 32-bit or 64-bit big-endian twos-complement integers and IEEE floating point numbers. Strings are represented as a sequence of non-null ASCII characters followed by a null, padded with enough extra null characters to make the total length be a multiple of 4 bytes. These representations facilitate real-time performance by eliminating the need to reformat received data. (Except for the unavoidable big-endian/small-endian conversion. We note that most small-endian machines provide special instructions for this conversion.)

The basic unit of Open SoundControl data is a message, which consists of the following:

- A symbolic address and message name (a string whose meaning is described below)

- Any amount of binary data up to the end of the message, which represent the arguments to the message.

An Open SoundControl packet can contain either a single message or a bundle. A bundle consists of the following:

- The special string "#bundle" (which is illegal as a message address)

- A 64 bit fixed point time tag

- Any number of messages or bundles, each preceded by a 4-byte integer byte count

Note that bundles are recursively defined; bundles can contain other bundles.

Messages in the same bundle are atomic; their effects should be implemented concurrently by the receiver. This provides the important service in multimedia applications of specifying values that have to be set simultaneously.

Time tags allow receiving synthesizers to eliminate jitter introduced during packet transport by resynchronizing with bounded latency. They specify the desired time at which the messages in the bundle should take effect, a powerful mechanism for precise specification of rhythm and scheduling of events in the future. To implement time tags properly, message recipients need a real-time scheduler like those described by Dannenberg [1].

Time tags are represented by a 64 bit fixed point number. The first 32 bits specify the number of seconds since midnight on January 1, 1900, and the last 32 bits specify fractional parts of a second to a precision of about 200 picoseconds. This is the representation used by Internet NTP timestamps [6]. The Open SoundControl protocol does not provide a mechanism for clock synchronization; we assume either that the underlying network will provide a synchronization service or that the two systems will take advantage of a protocol such as NTP or SNTP [7].

4 Addressing Scheme

The model for Open SoundControl message addressing is a hierarchical set of dynamic objects that include, for example, synthesis voices, output channels, filters, and a memory manager. Messages are addressed to a feature of a particular object or set of objects through a hierarchical namespace similar to URL notation, e.g., /voices/drone-b/resonators/3/set-Q. This protocol does not proscribe anything about the objects that should be in this hierarchy or how they should be organized; each system that can be controlled by Open SoundControl will define its own address hierarchy. This open-ended mechanism avoids the addressing limitations inherent in protocols such as MIDI and ZIPI [5] that rely on short fixed length bit fields.

To allow efficient addressing of multiple destination objects for parameter updates, we define a pattern-matching syntax similar to regular expressions. When a message's address is a pattern, the receiving device expands the pattern into a list of all the addresses in the current hierarchy that match the pattern, similar to the way UNIX shell "globbing" interprets special characters in filenames. Each address in the list then receives a message with the given arguments.

We reserve the following special characters for pattern matching and forbid their use in object addresses: ?, *, [, ], {, and }. The # character is also forbidden in object address names to allow the bundle mechanism. Here are the rules for pattern matching:

- ? matches any single character except /

- * matches zero or more characters except /

- A string of characters in square brackets (e.g., [string]) matches any character in the string. Inside square brackets, the minus sign (-) and exclamation point (!) have special meanings: two characters separated by a minus sign indicate the range of characters between the given two in ASCII collating sequence. (A minus sign at the end of the string has no special meaning.) An exclamation point at the beginning of a bracketed string negates the sense of the list, meaning that the list matches any character not in the list. (An exclamation point anywhere besides the first character after the open bracket has no special meaning.)

- A comma-separated list of strings enclosed in curly braces (e.g., {foo,bar}) matches any of the strings in the list.

Our experience is that with modern transport technologies and careful programming, this addressing scheme incurs no significant performance penalty either in network bandwidth utilization or in message processing.

5 Requests for Information

Some Open SoundControl messages are requests for information; the receiving device (which we'll call the Responder in this section) constructs a response to the request and sends it back to the requesting device (which we'll call the Questioner). We assume that the underlying transport layer will provide a mechanism for sending a reply to the sender of a message.

Return messages are formatted according to this same Open SoundControl protocol. There is always enough information in a return message to unambiguously identify what question is being answered; this allows Questioners to send multiple queries without waiting for a response to each before sending the next. The time tag in a return message indicates the time that the Responder processed the message, i.e., the time at which the information in the response was true.

Exploring the Address Space

Any message address that ends with a trailing slash is a query asking for the list of addresses underneath the given node. These messages do not take arguments. This kind of query allows the user of an Open SoundControl system to map out the entire address space of possible messages as the system is running.

Message Type Signatures

Because Open SoundControl messages do not have any explicit type tags in their arguments, it is necessary for the sender of a message to know how to lay out the argument values so that they will be interpreted correctly.

An address that ends with the reserved name "/type-signature" is a query for the "type signature" of a message, i.e., the list of types of the arguments it expects. We have a simple syntax for representing type signatures as strings; see our WWW site for details.

Requests For Documentation

An address that ends with the reserved name "/documentation" is a request for human-readable documentation about the object or feature specified by the prefix of the address. The return message will have the same address as the request, and a single string argument. The argument will either be the URL of a WWW page documenting the given object or feature, or a human-readable string giving the documentation directly. This allows for "hot-plugging" extensible synthesis resources and internetworked multimedia applications.

Parameter Value Queries

An address that ends with the reserved name "/current-value" is a query of the current value of the parameter specified by the prefix of the address. Presumably this parameter could be set to its current value by a message with the appropriate arguments; these arguments are returned as the arguments to the message from the Responder. The address of the return message should be the same as the address of the request.

6 Conclusion

We have had successful early results transmitting this protocol over UDP and Ethernet to control real-time sound synthesis on SGI workstations from MAX [9] programs running on Macintosh computers. Composers appreciate being freed from the limited addressing model and limited numeric precision of MIDI, and find it much easier to work with symbolic names of objects than to remember an arbitrary mapping involving channel numbers, program change numbers, and controller numbers. This protocol affords satisfying reactive real-time performance.

7 References

[1] Dannenberg, R, 1989. "Real-Time Scheduling and Computer Accompaniment," in M. Mathews and J. Pierce, Editors, Current Directions in Computer Music Research, Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, pp. 225-261.

[2] Freed, A. 1996. "Firewires, LANs and Buses," from SIGGRAPH Course Notes Creating and Manipulating Sound to Enhance Computer Graphics, New Orleans, Louisiana, pp. 84-87.

[3] IEEE 1995. "1394-1995: IEEE Standard for a High Performance Serial Bus," New York: The Institute of Electronical and Electronic Engineers.

[4] IEEE 1995b. "802.3u-1995 IEEE Standards for Local and Metropolitan Area Networks: Supplement to Carrier Sense Multiple Access with Collision Detection (CSMA/CD) Access Method and Physical Layer Specifications: Media Access Control (MAC) Parameters, Physical Layer, Medium Attachment Units, and Repeater for 100 Mb/s Operation," New York: The Institute of Electronical and Electronic Engineers.

[5] McMillen, K, D. Wessel, and M. Wright, 1994. "The ZIPI Music Parameter Description Language," Computer Music Journal, Volume 18, Number 4, pp. 52-73.

[6] Mills, D., 1992. "Network Time Protocol (Version 3) Specification, Implementation, and Analysis," Internet RFC 1305. (http://sunsite.auc.dk/RFC/rfc1305.html)

[7] Mills, D., 1996. "Simple Network Time Protocol (SNTP) Version 4 for Ipv4, Ipv6 and OSI," Internet RFC 2030. (http://sunsite.auc.dk/RFC/rfc2030.html)

[8] PCI 1993. PCI Local Bus Specification, Revision 2.0, Hillsboro, Oregon: PCI Special Interest Group.

[9] Puckette, M., 1991. "Combining Event and Signal Processing in the MAX Graphical Programming Environment," Computer Music Journal, Volume 15, Number 3, pp. 58-67.

[10] The USB web site is www.usb.org

[11] Yamaha 1996. "Preliminary Proposal for Audio and Music Protocol, Draft Version 0.32," Tokyo, Japan: Yamaha Corporation.

Publication Keywords

New Musical Control Structures from Standard Gestural Controllers

Mon, 09/21/2009 - 10:57 — AdrianFreed1 Introduction

Throughout history, people have adapted objects in their environment into musical instruments. The computer industry has developed the digitizing tablet (a.k.a. "artist's tablet") primarily for the purpose of drawing shapes in computer graphics illustration programs. These tablets are broadly available and low cost, and they sense many control dimensions such as pen or pointing device position, pressure, and tilt. We find that these controllers can be used for musical control in a variety of interesting and musically expressive ways.

2 Characteristics of the Wacom Tablet

We use a Wacom [9] ArtZ II 1212 digitizing tablet, a 12 inch by 12 inch model with both a stylus (pen) and a puck (mouse-like device) that allows two-handed input [7]. The stylus and puck are cordless, batteryless, and light weight. The tablet has a single DB-9 connector that carries both power and control information; on the other side of the cable is a mini-din connector suitable for the serial port on a Macintosh, PC, or SGI workstation. We've had no trouble running the cable at distances of about 30 feet.

The Wacom tablet accurately outputs the absolute X and Y dimensions of both the puck and stylus as integers in the range 0 to 32480. The stylus has a pressure-sensitive tip (and a pressure-sensitive "eraser" tip on the other end) that produces pressure readings in the range 0 to 255. When only the stylus is used, the Wacom tablet also outputs tilt values in two dimensions, in the range -60 to 60 degrees. Position and tilt are reported whenever the stylus or puck is in "proximity" of the tablet, within about a centimeter of the surface.

In addition to these continuous control variables, there are many ways to trigger events. The puck has 4 buttons, and the stylus has two buttons as well. Each tip of the stylus can be considered a button; pressing the stylus into the tablet will cause the same kind of button event. Another kind of event is generated when either device enters or leaves the proximity of the tablet. For the stylus, this event indicates which side (stylus tip side or eraser side) enters or leaves proximity.

It is important to evaluate the temporal behavior of computer systems for music [6]. We performed timing experiments on SGI machines using their fast UST clock, measuring the elapsed time between events reporting values of position, tilt, and pressure while continually moving the stylus so as to change each parameter constantly. The good news is that about 75% of parameter updates came within 1 ms of the previous update. The bad news is that the elapsed times greater than 1 ms averaged about 28 ms and were distributed more or less in a bell curve around 28 ms. The source of this erratic temporal performance seems to be context switches between the X server and our application program, a consequence of Wacom's decision to make tablet data available on Unix using X11 extension device valuator events. We expect that direct access to the serial stream from the tablet will address this difficulty.

3 A Model for Mapping Tablet Data to Musical Control

We have developed a model for mapping tablet data into musical control information (either MIDI or Open SoundControl [11]) that allows performers to simply customize the musical behavior of the tablet. In our model, the two dimensional surface of the tablet is populated by any number of arbitrarily-shaped polygonal regions. These regions can overlap, and they have a vertical stacking order that determines which of two overlapping regions is above the other. Each region has a user-assigned symbolic name.

The following events may occur in a region:

· Puck or stylus enters (or leaves) the proximity of the tablet in the region

· Either end of the stylus makes (or breaks) contact with the tablet

· Puck or stylus moves into (or out of) the region

· Button press (or release) while pen or stylus is in the region

For each region the user can define a list of actions to take when any of these events occur, e.g., the stylus tip touching the tablet in a region might cause a pair of MIDI note-on events.

There are also several continuous parameters that are updated constantly by the tablet:

· X and Y coordinates for puck and stylus

· X and Y axis tilt for stylus (when not using puck)

· Stylus pressure

Each of these continuous parameters can also be mapped to a list of actions, e.g., the X axis tilt might correspond to pitch bend.

What makes our model dynamic is that actions can be added to and deleted from these lists in response to events that occur in a region. For example, pressing a button while the puck is in a region could add a mapping from puck Y position to overall volume, and having the puck enter a different region could remove this mapping. This features facilitates complex musical behaviors in response to various gestures.

To allow the mapping of data values from one range to another we provide two primitives. The first is a linear scaling operator that implements functions of the form f(x)=ax+b where a and b are constant. The desired output range is specified; the system knows the range of possible input values and can compute a and b automatically. The second is stored function evaluation. We compute user-specified memoryless nonlinear functions with an abstraction that subsumes table lookup, expression evaluation, neural network forward-pass, and other techniques. Of course the tablet itself is an excellent tool for drawing function curves.

One important feature of the tablet is that its position sensing is absolute rather than relative. This means that the performer does not need any visual feedback from a computer monitor to see which region the stylus or puck is in. The Wacom tablet has a clear plastic overlay under which paper and small objects may be placed. We can print a "map" of the user's defined regions to the scale of the tablet and place it under the overlay; this lets the user see exactly where each region is on the tablet. Removable adhesive strips for drafting may be used to create surface irregularities offereing tactile feedback.

4 Examples

4.1 Digital Tambura Interface

Our first use of the digitizing tablet for musical control was to create an interface for a drone instrument similar in function to the Indian tambura. A real tambura has 4 strings with no fretboard or fingerboard; the player plucks each open string and lets it ring. Tambura players typically pluck the 4 strings one at a time and then start over at the first string, providing a continuous drone.

A tablet interface was designed that retains features of the playing style of a real tambura. We defined six regions on the tablet corresponding to six virtual strings. Each of these virtual strings had a corresponding monophonic synthesizer voice set to a particular drone timbre and pitch. The action of touching the stylus to the tablet in a particular region represented touching a finger to a real string: it caused the currently sounding note on that string to decay fairly rapidly. Releasing the stylus from the tablet represented the second half of the pluck, where the finger releases the string and sets it vibrating. This caused the voice to start a new note.

The loudness of each note was determined by the total amount of horizontal distance traveled between the time the stylus touched the region and the time the stylus left the tablet. Timbral control came from a mapping from the X axis position at the time the stylus left the tablet to the relative balance of even and odd harmonics in the synthesizer [5].

4.2 Strumming

We use the tablet to emulate the gesture of strumming a stringed instrument. We define four to ten thin rectangular horizontal regions which represent virtual strings much as in the tambura example. Again, each of these regions has a corresponding synthesizer voice which is virtually plucked in two steps by the stylus entering and then leaving the region. The speed of the pluck (i.e., the reciprocal of the time between when the stylus enters and leaves the region) combines with the pen pressure to determine the loudness of each note.

When the upper stylus button is depressed the stylus' function changes from exciting the virtual strings to muting them. In this case, the note for each string still decays when the tablet enters the region, but a new note does not start when the string leaves the region. The middle button corresponds to a "half mute" mode where the synthesized sound is more inharmonic and each note decays faster, corresponding to the playing technique on real strummed instruments of partially muting strings with the palm.

On real stringed instruments, the position of the picking (or plucking or bowing) along the axis of the string is an important determinant of timbre. We emulate this control by mapping the X position at the time the stylus leaves the string region to a timbral control such as brightness.

We have several techniques for controlling pitch with the puck in the left hand. The first is modeled loosely on the autoharp. There are regions of the tablet that correspond to different chord roots, and each of the 4 puck buttons corresponds to a different chord quality (e.g., major, minor, dominant seventh, and diminished). Pressing a button with the puck in a particular region determines a chord, which in turn determines the pitches of each virtual string. The layout of chord regions and chord qualities, and the voicings of each chord are all easily configurable for different styles, pieces, or performers.

Another technique for pitch control is modeled on the slide guitar, with the puck taking the role of the slide. In this case the pitches of the virtual strings are in fixed intervals relative to each other, and the puck's horizontal position determines a continuous pitch offset that affects all the strings. When the puck is not in proximity of the tablet the strings are at their lowest pitches, corresponding to strumming open strings on a slide guitar. The buttons on the puck select from among a set of different tunings.

4.3 Timbre Space Navigation

CNMAT's additive synthesis system provides timbral interpolation via the timbre space model [10]. The tablet is a natural way to control position in a two-dimensional timbre space.

The simplest application uses the tablet in conjunction with another controller like a MIDI keyboard. In this case the job of the tablet is just to determine position in the timbre space, so we map the two position dimensions to the two timbre space dimensions and use the other controller to determine pitch, loudness, and articulation.

Another approach is to use both hands on the tablet. The stylus position determines timbre space position. When the stylus touches the tablet a note is articulated, and when it leaves the tablet the note ends. Stylus pressure maps to volume. The puck, held in the left hand, determines pitch via a variety of possible mappings.

A third approach is to implement a process that continually produces a stream of notes according to parameterized models of rhythm, harmony, and melody. The left hand can manipulate the parameters of this model with the puck while the right hand navigates in timbre space with the stylus.

5 Future Work

We would like to be able to recognize various kinds of strokes and gestures made with the stylus. Previous work on stroke recognition in the context of computer conducting [2] seems applicable, as does work on the integration of segmentation, recognition, and quantitative evaluation of expressive cursive gestures [8].

6 Conclusion

The tablet interface provides a musically potent and general two-dimensional interface for the control of sound synthesis and compositional algorithms. With the addition of stylus pressure and tilt, two additional dimensions are available for each hand. Our experiments have demonstrated that irregularities can be added to the surface providing tactile reference. The tablet interface is basically a spatial coordinate sensor system like the Mathews Radio Drum [1], the Buchla Lightning [3], the Theremin [4], joy sticks, and other sensor systems like ultra sound ranging. But, unlike some of these systems it offers the possibility of tactile reference, wide availability, flexible adaptation, precision, and reliability. The tablet interface and its spatial coordinate sensor cousins offer the possibility of long-lived alternative musical control structures that use mathematical abstractions in a reliable manner as the basis for a live-performance musical repertoire.

7 Acknowledgments

CNMAT gratefully acknowledges the support of Silicon Graphics, Inc., and Gibson Guitar Corporation for generous contributions that supported this work.

References

[1] Boie, B, M. Mathews, and A. Schloss. 1989. "The Radio Drum as a Synthesizer Controller," Proc. ICMC, Columbus, Ohio, pp. 42-45.

[2] Brecht, B., and G. Garnett. 1995. "Conductor Follower," Proc ICMC, Banff, Canada, pp. 185-186.

[3] The Buchla and Associates web site describes Lightning II: http://www.buchla.com/

[4] Chadabe, J. 1997. Electric Sound: The Past and Promise of Electronic Music, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

[5] Freed, A. 1995. "Bring Your Own Control to Additive Synthesis," Proc ICMC, Banff, Canada, pp 303-306.

[6] Freed, A. 1997. "Operating Systems Latency Measurement and Analysis for Sound Synthesis and Processing Applications," Proc. ICMC, Thessaloniki.

[7] Kabbash, P, W. Buxton, and A. Sellen. 1995. "Two-handed Input in a Compound Task," Proc. SigCHI, Boston, Massachusetts, pp. 417-423. http://www.dgp.utoronto.ca/OTP/papers/bill.buxton/tg.html

[8] Keeler, J., D. Rumelhart, and W. Loew. 1991. "Integrated segmentation and recognition of hand-printed numerals," In R. Lippmann, J. Moody, and D. Touretzky, Editors, Neural Information Processing Systems Volume 3, San Mateo, CA: Morgan Kaufmann.

[9] The Wacom WWW site is www.wacom.com

[10] Wessel, D. 1979. "Timbre Space as a Musical Control Structure," Computer Music Journal, Volume 3, Number 2, pp 45-52.

[11] Wright, M., and A. Freed. 1997. "Open SoundControl Protocol," Proc ICMC, Thessaloniki. New Musical Control Structures from Standard Gestural Controllers, , International Computer Music Conference, 1997, Thessaloniki, Hellas, p.387-390, (1997)